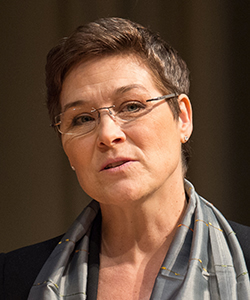

A Discussion with Karin Ryan, Senior Adviser for Human Rights, The Carter Center

With: Karin Ryan Berkley Center Profile

March 5, 2015

Background: Karin Ryan is a pioneer and leader in human rights, with a long-standing and central role at the Carter Center. Former president Carter’s 2014 book, A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power, is dedicated to her. In early February 2015 Karin led the Human Rights Defenders Policy Forum at the Carter Center with the theme focused on women, religion, violence, and power. She spoke on March 5, 2015 with Katherine Marshall by telephone about what drives and inspires her in this work. Their discussion explored the culture of violence in American society, especially, and its effect on the broad patterns of violence against women, both in the United States and beyond. She discusses how women’s rights need to be advanced in this broader context of human rights overall rather than as a niche, separate issue.

How did you come to your sharp current focus on issues of women’s rights, violence, and religion? How do you see religion as part of the challenge?

I grew up as, and am now, a Baha’i. Thus I grew up in a community that was very concerned with human equality, including equality between women and men. The enduring Baha’i image is that mankind is like a bird, with one wing female, the other male. Unless both are equally strong, the bird cannot fly. Thus equality was not just assumed; it was always emphasized. My mother was a single mother, raising three girls. She rose through on-the-job training and sheer hard work to become a highway engineer for the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans). Thus I came into this work with a mindset that equality is very central. It is natural to what we have to achieve no matter what the endeavor.

And that is also natural at the Carter Center. President Carter is a person of great personal faith. He is never awkward about it and never unsure in his conviction that faith is a way to advance human rights. That belief has been central to his roles and convictions as a political leader. Thus it has been an easy connection to make as we pursue human rights. Further, there has always to be a clear alignment between the pursuit of human rights and his faith. It is foundational, almost automatic, for those of us here at in the Human Rights Program.

Of course, that is not the way it is in the larger world. There is a large division that separates church and state. The American republic was formed on such a strict separation, for good reasons. As a society we have not quite recognized the way in which these ideas (faith and human rights) can be mutually supportive without undermining the separation, avoiding abuse of power, or an inappropriate emphasis of one belief over another. We have become used to this strict division. And the human rights framework is in some ways a sort of a secular religion, with its belief system, rules, codes, and so forth. It comes with duties and obligations.

Yet what is interesting is that many who framed modern understandings of human rights relied on religious doctrine and ideas and even language to craft the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Atlantic Charter, which was its predecessor. It is founded on lofty spiritual concepts of equality and oneness before God, adapted into a secular framework that would be acceptable to people of all beliefs. It was ingenious to cite and reference lofty language and put it in universal terms that persons of many beliefs can accept.

The human rights system has been built around the amazing work of putting together global treaties that elaborate on these rights and obligations, so that they are codified in a long series of treaties. It stands as a monument to human achievement. As hard as it has been to create global agreement around human equality, it reflects the best effort as human beings to articulate God’s mandate for human equality into an enforceable system.

But the question remains, how to enforce it? How to enforce the idea that the Creator has exhorted all human beings to treat each other as we would wish to be treated? How do we take that, make it concrete, and thus enforceable? That is what the decades of hammering out—declarations, treaties, covenants, etc. on torture, women, children, and other subjects—have been about. The process reflects the view that all human beings must make their best effort to create a system that supports God’s commandment that we treat each other with equal dignity. It is impressive as a human achievement. Despite vast disparities, conflicts, territories shifting, militaries, global powers, direct violence, anxiety and tension, it has progressed. Behind so many global tensions, underneath, humankind has been making its best effort to create and live into a global structure that will restrain our worst instincts for violence, that will force respect for one another. In this tug of war, we can see a great achievement that reflects who we are and what we deserve, as well as the push and pull of geopolitics and political power.

And right now we are seeing the issue of religion rear its head very dramatically. It may be because of a failure to see and accord its due place, to appreciate how it influences the thoughts of each of us, citizens and leaders, as believers in something greater than themselves.

How has religion become so central to the Human Rights Defenders Forum (which has run since 2003)?

It began in 2007 with our forum called “Faith and Freedom: Human Rights as Common Cause.” We brought people of faith from Haiti, Palestine, Israel, America, Colombia, Malaysia, many countries. This is how we met Zainah Anwar from Sisters in Islam, an organization that explicitly examines Islamic concepts through a human rights lens. Then, President Carter gave a major speech to the Parliament of World Religions in 2009 where he explained his own journey as he has sought to align his faith with his commitment to equality. He described the decision that he and his wife Rosalynn made to split with the Southern Baptist Convention in 2000 when the organization ruled that women could no longer serve in church leadership and that women should be subservient to their husbands. At first, U.S.-based human rights organizations were reluctant to participate in this discussion, as they feared that bringing religion into the conversation would inevitably lead to an embrace of cultural relativism and a weakening of human rights demands. President Carter took a very affirmative position on this question, insisting that while carefully selected texts can be used to make any argument, the overall spirit of all Holy Scripture is equal dignity and rights before God. This affirmation has been repeated in each subsequent meeting and has helped reassure human rights advocates who had been skeptical.

The focus on religion has increased over time, both in meetings and as a result of the online platforms. In a recent exchange involving participants from Iraq, Jeremy Courtney, from the Pre-Emptive Love Coalition, talked about how there is no way to ignore the religious dimension to what is happening in the world. And so we asked, what should we do? The answer seemed to be to acknowledge each other also in religious terms, to understand that many of us involved are believers in something greater than ourselves, that we believe in far more than the small, human concerns that get us into war, including the build up to wars. Jeremy emphasized this point about Iraq—that we truly need to see all of its people as human beings. We have to acknowledge each other as believers in something. If we allow ourselves to see our commonality we can make progress.

What makes human rights so controversial?

The divisions we have created around human rights come, I believe, from the fact that human rights is based on laws and rules that must be passed and enforced. This is obviously a necessary aspect of progress. But religion and culture are very influential and often hold more power than law. I think that the current state of affairs should encourage us to do anything possible to ensure that we allow for a space wherein we see others as believers in something higher. Some are believers in a particular religion and some believe in a humanist ethical framework. These do not have to be in competition with each other if we all agree that progress can be gradual and sometimes too slow for our liking, but that we have to persist. We need to focus far more on the common problem that we are all in struggles for power, geopolitical considerations, and resource wars that keep us in violence.

I am fearful of what I see as a backlash against women’s rights. Is this a concern you share?

Yes. And there are many causes.

We always start from a framework of human rights broadly. There is a danger in carving out something and thinking that it can be done in itself. That includes women’s rights.

Let me give a concrete example. When we first started engaging post-revolution in Egypt, a first question we asked was how we could support progress on women’s rights globally and also locally in places like Egypt. We put forward the idea of a conference on women’s rights in Cairo. However, most of our partners said that we should not do it in Cairo, especially as an American organization. They reminded us that women’s rights had been Suzanne Mubarak’s focus, and she was closely aligned with American policies in the region that had been discredited by the revolution. Egyptian feminists had worked for rights for a long time and great progress had been made, for example on the divorce laws and outlawing genital cutting. However, it was done in a way that was not in concert with broader progress on human rights. One influential woman was able to push through things, but because action was not happening simultaneously within the broader framework of pursuit of human rights, action at this point would be susceptible to the accusation that we were advancing a Suzanne Mubarak agenda, and that that was an American agenda.

There are similar issues around the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. These were presented as supporting the promotion of democracy and women’s rights and that the military presence was to protect women’s rights. This has become dangerous—seeing a military presence as a proxy for advancing women’s rights. Wherever I go I hear this, and it is clearly why there is a backlash. We have a situation where military action, invasions, and a military presence globally are somehow linked to our pursuit of women’s rights, at least in the perception of local actors who would be natural partners in any global human rights movement. In the Middle East, the American military presence is indeed noticed. There is always this concern about military action, and any action program, no matter how worthy, that could come about through military action. When Boko Haram kidnapped the Chibok girls and the U.S. offered military support, the question was asked, “Is this a stepping stone into widening the war and enlarging a U.S. military presence?” That kind of reaction is not helpful to us as we seek to build democracy and advance human rights, including women’s rights.

I believe that in order to really pursue advancement of women’s rights in cooperation with local communities, we must listen to their concerns, which include concerns about America’s “realist” agenda. They will always want help. Right now, they might want troops in Iraq because their cities are under threat from so-called “ISIS.” But that is a tactical matter related to immediate needs. If we were to think about what is in the interests of advancing rights of women where it needs to happen, we have to be prepared to look at what is causing the backlash and bitter feelings.

One real fear arises if support for women’s rights comes along with support for dictatorships. In Tunisia, women’s rights were advanced in many respects, but against the backdrop of a terrible human rights record, going back to the post-colonial period. Like in Egypt, there were crackdowns on human rights more broadly and failure to deliver tangible economic and social progress, that created conditions within which conservative Islamist movements gained credibility and support. This phenomenon has been called “large group regression” in which a group retreats into more traditional, conservative behavior as a result of being attacked from outside.

Another factor is a fear of modernity in conservative cultures. American and Western cultures are seen by many as intrusive and frightening. Hyper-sexualized and violent content in the media, added together with other backlash against dictatorships, creates a volatile mix.

It is difficult to pursue a plan or to carry out a program to advance the rights of women and girls without understanding and being prepared to address and confront these and other factors that create resistance. A key question is how local communities view those of us in the west. We see tensions involving wonderful, dedicated western organizations committed to human rights, working on familiar naming and shaming strategies that have succeeded in some contexts but might cause backlash in other contexts. Such strategies, while important and worthy of support, can complicate and make the situation even more dangerous for the women they are trying to help. It is vital to develop complementary strategies that include working through community dialogue, taking approaches like that of Tostan in West Africa. These inside-out approaches, “community-led development,” can take longer to produce results, but they work—Tostan has seen their programs achieve unprecedented decreases in female genital cutting, domestic violence, child marriage, and other related outcomes. This can create a dilemma in terms of which strategies to use. I hope that The Carter Center’s Forum can serve as a conduit through which these various efforts can be examined and better coordinated.

What about looking at it from the American culture angle?

Nothing is going to happen to change the American lifestyle! Our entertainment includes content that is considered obscene in some cultures—that is not going to change. It is the volatile mix with military intervention that exacerbates the situation. There can be good programs that reach out, facilitate understanding, and that are not tainted with relativism. But we need to enter into programs in a spirit of co-creation, with a respectful attitude. An example is the way that Tostan brings human rights into the work in a natural and respectful way that makes everyone feel included and safe, confident that we will not yank their children around or use them as props in campaigns that are developed externally. There is a lot of room for collaboration, but we have to approach the relationships with mutual respect and good communication.

So what is the approach that you think can help us to advance?

We need to look at an approach where two streams must proceed in parallel. We need to work to remedy the immediate suffering. We need better laws on sexual assault on campuses; we have simply got to do that. As Senator Kristen Gillibrand recommends, we have to take commanders out of the line in prosecution of assault cases in the military. In Nigeria, we need to support communities in meeting their immediate needs, and seek action to protect girls from being abducted by Boko Haram, for example. There is no doubt that we must do that.

The danger is that we are all so busy responding to these immediate preoccupations that we forget the central need for this deeper commitment to long-term solutions. We need to commit over the next generation to ask these larger questions. What are we doing that is creating a backlash (i.e. invading countries in the name of democracy)? What action are we taking? How are we advancing human rights broadly?

In 2003, 12 years ago, when we launched the Human Rights Defenders Forum, we explored how counterterrorism efforts we were using, including crackdowns on the press and activism and the overall war on terror, would have a backlash effect. Willy Mutunga was with us—he is now president of the Supreme Court of Kenya. He spoke about our worry that abusing human rights in the name of terrorism would fuel terrorism in his country, which had just had its first free election. And that is exactly what is happening now. We have used and are using military practices in ways that fuel terrorism—Al-Shabab was a small fringe group in Somalia before Ethiopia and the U.S. launched military operations against the group. This development led to a increase in their ability to recruit fighters—it was these fighters who carried out the horrific attack in 2013 on the Westgate shopping mall in Nairobi. Al-Shabab spokespersons stated that this attack was in retaliation for Kenya’s military operations in Somalia. Military operations do not appear to have worked in Somalia, Yemen, etc., but certainly inflame the situation.

In short, we have to do both: react to the immediate and include in our reflection and strategy actions that take into account what our actions are contributing to in the long term.

How do you see media and communications relating to these challenges?

In November, 2013, the American Bar Association and the Carter Center held a conference on the death penalty. In the news a study reported homicide rates just around the time of an execution, just before, and just after. The reported results showed an increase just after an execution. It was a small study, a limited number of cases due to the small number of executions, but there was a correlation. A message we took from it was that when the state kills, when violence is so normal in how we deal with social matters, violence is likely to increase. And this normalization of violence is indeed increasing in our society. You do not need to be a social scientist to draw the conclusion that violence will increase everywhere. Normalized violence is leading to more violence, yet we do not even even see it as problematic.

I worked recently with President Carter on a piece for the Lancet, on violence against women and public health. Among the different factors we were looking at were violence and video games. The numbers are startling; more than 90 percent of teens today play video games every day for hours. And these games have constant violence, war games, hideous violence, simulated and real seeming. There are unbelievable story lines centered on violence against women. Anita Sarkeezian has highlighted this. The characters do not even have names. They are decorations, props for violence. There was a woman I watched in one game whose body was mangled in a gear thing into meat so a guy could go through to the next level. I was shocked. I have boys and we had a big discussion about this. It is simply not credible to think that this does not influence attitudes. Different studies show different outcomes, with contradicting inferences.

In a parallel vein, what is happening with campus sexual assault is disturbing. Studies show one in five women will experience sexual assault during her four years of college, yet there is near total impunity for rapists, both students and faculty.

We are at war, actively, and our government has chosen to wage a war that is so destructive. Look at the immediate discussions about Iran. We actually see Prime Minister Netanyahu speaking to the U.S. Congress, arguing that we will have to go to war to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons. Why are we not also discussing the need for implementation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty—that we should be advancing a more mutual process towards disarmament? Do we have any notion of what it would involve to go to war with Iran? Any concept? This can surely be linked to the loose talk about violence in our culture. It is hard to believe that does not influence us.

How do you see this prevalence of violence in our culture relating to violence against women?

I had a haircut just before the Human Rights Defenders Forum. My hairdresser asked what it was about and I told her that it focused on violence against women. “What does that mean? Rape?” she asked. “Yes.” I answered. So she began to ask what we might consider rape. What if you don’t want to have sex, were forced, felt sick about it. Is that rape? Yes, I answered. So this young woman went on saying that this had happened several times, and then spoke about how, when she was 12, her uncle forced her and she had never told anyone because she was ashamed. She’d never told anyone before telling me. My reaction is, “How amazing?! This is happening all the time.”

So what can we do? One way is to have effective and pervasive messaging that gives people the stage to speak. The problem is that it is so full of shame. Sexual harassment is so common. The new film Hunting Ground was made by the filmmaker who made Invisible War about sexual assault in the military. It examines the epidemic of sexual assault on campus. It is so well done and goes into it in detail. It brings out the situation that faces someone, asking “What do I do?” If they speak to someone, the answer they get is “Don’t tell anyone.” How many women have to tell the same story before someone is compelled to deal with what he did? Look at the Cosby case.

If a woman accuses someone of violence, one step we can take is that that person should be automatically believed. That does not mean that the person accused is automatically guilty. But we have to make sure that anyone making a claim is heard, and that there is an investigation immediately. We cannot have false reporting and need to make sure that there are top-notch investigative resources. I have sons and would be horrified if one were accused and his life ruined without due process. So we need to organize ourselves around a better system that makes sure that if someone says “I have been violated,” resources are made available to them and also to those accused so they can defend themselves. The key is to have resources so investigators can do what they need to do, with proper questioning that makes it possible to gets to the bottom of things. It can be done.

Every problem has that kind of solution. That is even true in an extreme situation like the horrific rape case in India. Many factors were at work there: the bus system and public infrastructure, including lack of police support, public attitudes, even religion. But the common attitude that it is her fault must be confronted, especially by religious leaders, in every way possible. We need to work on attitudes and on public safety (for example cameras on buses and in public space, adequate police training, etc). All those steps involve decisions and politicians can make sure there is an infrastructure for justice. Every problem has a remedy. Each sector needs to do its part—government, public figures, religious leaders, activists. It’s an area where we simply must learn and must act.

Your interest in music is clear both from your bio and from the Human Rights Defenders Forum. How did you come to it? It resonates for me because of my long-standing involvement with the Fes Festival of Global Sacred Music and its Forum, which set out deliberately to use music as a bridge among cultures.

I studied in Boston at the Berklee School from 1999 to 2003. I was looking for ways, including orchestration and production, to use music. We are all about communicating, and especially communicating ideas. Music is such a powerful tool to communicate. I wanted to have a framework to allow me to delve deeper into it. And as you saw at the Forum, when it is possible to bring music and ideas together, the leverage is very powerful!