Challenges to Educational Equity in Nepal during the COVID-19 Crisis

By: Tierra Hatfield

January 5, 2022

The COVID-19 pandemic and economic shocks related to containment measures have increased both the visibility and consequences of social justice issues in education in Nepal. In the capital of Kathmandu, extensive lockdowns in 2020 and surges in COVID-19 cases in the beginning of 2021 exacerbated educational inequalities and digital divides, leaving many students out of school as educational institutions scrambled to respond to the pandemic.

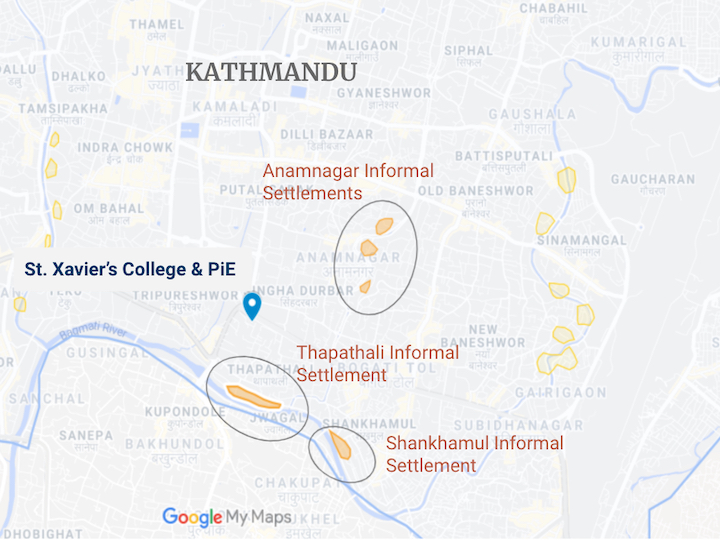

Guided by its Jesuit value of service to others, St. Xavier’s College’s Partnership in Education (PiE) program—a free education and tutoring program—is responding to the crisis by filling education gaps and supporting marginalized youth. For many marginalized youth from informal settlements and low-income areas around Kathmandu Valley, PiE has become their only source of education during the pandemic. In interviews, PiE students, parents, and trainees share the social justice issues they face during the COVID-19 pandemic—highlighting how financial struggles, the growing digital divide, and the challenges of connectivity are impacting marginalized youth.

This research study combines a desk review of situational reports on the COVID-19 situation in Nepal and primary data from 17 key informant interviews with the PiE community. To capture the diversity of experiences across the community, semi-structured interviews were conducted with PiE staff, trainees, and volunteers, as well as with parents of current and past PiE students. Due to pandemic-related movement restrictions, all interviews were conducted virtually between January 2021 and May 2021, with the assistance of St. Xavier College staff and a translator. This research does not seek to provide all the answers to the complex issues surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and education in Nepal. It does, however, seek to shed light on the social justice issues facing the PiE community and to elevate the voices of individuals who have been disproportionately affected by the crisis.

The COVID-19 Situation in Nepal

Nepal has been one of the countries hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic in South Asia, with the highest levels of cases recorded in the Kathmandu Valley and southwestern regions that border India. In addition to the direct impacts of the pandemic on the health sector, government-enforced containment measures have amplified economic inequality and social disparities across the country. According to a survey conducted by the World Bank, more than two of every five economically active workers reported an incidence of job loss or prolonged work absence in 2021.

Map of the Kathmandu Valley showing the boundaries of Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur, highlighted in blue. The red blocks on the full map of Nepal indicate other major cities in Nepal. The left-inset map shows the location of Nepal in South Asia. (Source: Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences)

All educational institutions in the Kathmandu Valley were abruptly shut down in March 2020 just as students were approaching year-end examinations. In February 2021, a lift in the lockdown allowed some schools and universities to resume in-person classes. However, the reopening was short-lived, as the government announced another lockdown in April 2021 in response to a second wave of the virus. Although Nepal has achieved considerable progress in education indicators in the last two decades, extended closure of schools and universities over the last year has exacerbated lingering structural social and educational inequalities. St. Xavier’s College, a private Jesuit higher education institution, is among the universities and schools in the Kathmandu Valley facing the challenges and impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on the Nepali education system.

St. Xavier’s College and the Partnership in Education Program

The Jesuits began their educational work in Nepal in 1951 with the opening of the first Jesuit primary school on the outskirts of Kathmandu Valley. Prior to the end of the Rana monarchy in 1951, education was only available to the wealthy and the elite. The new democratic political system established in 1951 was the first push to create schools for the general population and to allow women in Nepal to get an education. The Nepal Jesuit Society was formed and expanded schools and universities throughout Nepal, including St. Xavier’s College, Maitighar (SXC) in Kathmandu Valley, established in 1988.

Building on the St. Xavier’s College main campus located in Maitighar, Kathmandu. Photo provided by St. Xavier’s College.

St. Xavier’s College offers secondary education in the form of a Plus Two program (Grades 11 and 12) [1] and a UK-affiliated Advanced Level or A-Level program [2], and tertiary education through several undergraduate and postgraduate programs. Guided by the Jesuit values of educational excellence, leadership, and service to others, its programs integrate academic work with physical, spiritual, and emotional development through various co-curricular activities. While there is a focus on Jesuit values, the program welcomes people from all religious backgrounds, and approximately 98% of students are non-Catholic (interview, Fr. Jiju Varghese, S.J., April 6, 2021).

Although the college is a private institution established and managed by the Nepal Jesuit Society, it is also uniquely connected to public government schools through its Social Work Department and its commitment to community service. Embodying its motto, “Leadership in Service to Others,” St. Xavier’s Social Work Department runs an innovative outreach program: Partnerships in Education (PiE), which seeks to lift up children in the lowest income brackets in areas surrounding the campus by providing free educational classes and development activities.

Established in 2004, the PiE program is guided by Father Jiju Varghese, S.J., principal at St. Xavier’s College, and run by St. Xavier’s student trainees in the Bachelor in Social Work (BSW) program and volunteers from the A-Level and Plus Two level programs. PiE offers free educational classes to between 60 to 90 marginalized students in public government schools, specifically those whose education is impacted by poverty. Students served by PiE are enrolled in primary level (Grades 1–5) and lower secondary level (Grades 6–8) classes in different public schools around Kathmandu Valley and are between 7 and 16 years old. Many of the PiE students come from the Thapathali slum area, one of the most populated and neglected settlements in Kathmandu Valley [3].

St. Xavier’s vision for the PiE program is to empower students from marginalized communities by providing tutoring and supplemental educational classes, as well as supporting the students’ interpersonal development. PiE trainees and volunteers work with the students to build their confidence in public speaking and to foster their creativity through engagement with poetry, art, and drama. On Saturdays, the PiE program hosts extracurricular activities, such as basketball, table tennis, picnicking, dancing, and singing.

The classes were not only about academics... [we] got engaged in social activities such as sharing our opinions on some topics, discussing something, or playing games, or something like that, and that really encouraged us to speak out in our group and also develop ourselves (interview with Bibek Pariyar, previous PiE student and trainee, April 28, 2021).

The program also conducts regular home visits, where SXC trainees and volunteers meet with the families of their PiE students to gain a better understanding of each student’s unique background and needs. The visits allow SXC trainees and volunteers to connect with each student’s parents, talk about the student’s academic progress, and build a support system for each student to achieve their full potential both inside and outside the classroom.

PiE : Sowing Dreams | St. Xaviers College, Maitighar. This six-minute video was published in January 2017 by St. Xavier’s College showing the day in the life of a PiE student at SXC prior to the pandemic. The video explains the mission behind the program and interviews PiE students about their experiences at PiE.

I am happy that they visited… because I didn't have a lot of visitors interested in me and my family, and it was good to know they were welcoming and that they wanted to know about me and that [they] really cared (interview with Bibek Pariyar, previous PiE student and trainee, April 28, 2021).

The program also allows SXC students to get hands-on experience in social work and to practice teaching and leadership skills as they work with young PiE students from informal settlements and public government schools. SXC students in the BSW program receive fieldwork credit for volunteering to teach in the PiE program. Furthermore, some of the marginalized youth enrolled in the PiE program end up getting into SXC’s Plus Two and undergraduate programs, and many go on to become PiE volunteers and trainees themselves.

Jesuit Approaches to Education

At the heart of the PiE program is the Jesuit dedication to holistic growth and the idea of education as preparation for life and life-long learning. The SXC motto, “Dedicated to Excellence, Leadership, and Service,” emphasizes the measurement of a successful Jesuit education in terms of not only academic performance but also personal development and leadership in service to others. The college also embraces the motto established by the Jesuits in Nepal, “Live for God and Lead for Nepal.” For SXC, the motto signifies the incorporation of spirituality into everyday life and personal responsibility to the country. This value framework is passed down to the PiE program.

This figure represents the three pillars of the PiE program as interlocking gears: educational support and tutoring, personal development and social activities, and home visits.

In interviews, PiE trainees and volunteers conveyed the Jesuit values of service to others and leadership in the ways they described their role in teaching and mentoring. It is also clear that SXC students have a deep sense of care toward the marginalized youth in the program. For instance, several SXC students emphasized that they encourage the PiE children to explore their own abilities and talents in order to foster their confidence and independence, helping them achieve goals both inside and outside the classroom.

I remember one of my students, she really liked dancing and her parents were not really open to the idea of sending her to the dance class, because [they thought] she's going to get more distracted if she was in dance classes. But then we went for a house visit and we said that if [they] send her to dance class... then maybe she would be more motivated to improve her studies. We felt that home visits [were] definitely really helpful (interview with Adwitia Grung, previous PiE trainee, April 20, 2021).

Previous PiE students and some parents of current PiE students also expressed appreciation for the characteristics of wholesomeness, integrity, and collaboration that are integrated into the program. In an interview, the parent of two current PiE students, Marni Devi Yadav, expressed that her “children [have] improved in their academics and also in general... as they have increased their communication skills and that's how they're growing through [the program]” (interview, April 27, 2021).

Social Justice Issues Facing the PiE Community

Throughout Nepal, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted marginalized communities in the lowest income brackets and exacerbated social justice issues related to access to education. In interviews, PiE students, parents, and trainees and volunteers identified the major social justice issues facing PiE students and their communities. In every interview, the four biggest issues were identified as (1) socioeconomic hardship due to COVID-19 containment measures, (2) the digital divide, (3) inequalities between public and private educational responses to the pandemic, and (4) mental health. All of these factors have amplified barriers to education for many marginalized students in Kathmandu Valley, disproportionately impacting children from low-income families and those from the settlements.

Socioeconomic Hardship

Arguably the biggest issue contributing to barriers to education for PiE students and their communities is the financial crisis created by efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result of lockdown measures, lower-income families are losing their primary sources of income, housing, and jobs. While COVID-19 is the primary causal mechanism, the magnitude of its impact highlights the underlying challenges of structural poverty and social exclusion linked to caste and ethnicity.

PiE students and their communities are particularly impacted by the interaction of COVID-19 with underlying social injustices and inequality. Several PiE trainees said that many students, especially those in public government schools, either have not been able to access consistent education or have not rejoined school at all since the initial lockdown in March 2020, citing increased financial hardships as the primary challenge. Financial hardship has affected all levels of the community and comes in many different forms, from not being able to pay for data, technology, or school tuition, to losing jobs and housing and needing to relocate to rural areas.

During the lockdown, we obviously had a lot of facilities, as a middle-class family, compared to what the [PiE] children have, so I was really worried about how the children and their families were. Because even on normal days it was hard for them to, you know, get by with their daily meals and daily expenses, so I could only think how hard it must be for them now (interview with Adwitia Grung, PiE trainee, April 20, 2021).

A parent with three children in the PiE program, Kamala Bhattarai, said that her family was forced to move out of their one-room apartment in Kathmandu after losing their primary source of income. They moved back to their parents’ home village in rural Nepal, where there was no internet, and their children were unable to access online classes to continue their studies. Bhattarai shared, “I did not have any money to put the data for joining the classes, and it was very difficult for my family, and, you know, many of the classes were missed” (interview, April 20, 2021). Many families face a similar situation, and with the reintroduction of a country-wide lockdown in March 2021, many children have been unable to attend school for over a year.

For families who remained in Kathmandu, the disruption to the labor market, specifically the urban informal sector, combined with the high cost of living in Kathmandu, has made education in the time of COVID-19 unaffordable. The majority of PiE students come from families who rely on informal sector jobs as their primary source of income—these jobs lack basic social protections, meaning many PiE families are increasingly at risk of poverty. Many who remained in Kathmandu were not able to afford school tuition or the data and technology required to access online classes.

The Digital Divide

One of the most significant ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on education has been the increased significance of access to computers, the internet, and technological knowledge. In Nepal, the digital divide between those who have access to technology, internet, and data, and those who do not, has further exacerbated educational inequality. The lack of access is directly linked to the financial crisis. However, it also highlights underlying rural-urban and socioeconomic class divides within Nepali society. For PiE students and families, the lack of access to technology and data has been a major challenge during the pandemic.

Chanchali Lama, a PiE parent with two sons in the program, Grades 2 and 4, explains that her children are also not able to regularly attend online classes during the pandemic. Although her children’s public school has started remote learning and online classes, her family has only one mobile device, and the data she needs to buy for the cell phone is expensive. Therefore, only the eldest child in Grade 4 is able to attend some remote learning classes. Her younger child sometimes goes to his friends’ or cousins’ houses to watch his online classes on their cell phones, but when he is at home, he does not attend classes.

The government school ran online classes, but I don't think it was effective for some of the families, because all families do not have mobile phones that could be used to join these classes (interview with Bibek Pariyar, PiE trainee, April 28, 2021).

The lack of mobile phones and devices to connect to online classes has significant implications, as families are forced to decide which of their children will take online classes. Faced with this challenge, usually, only the eldest children will use the family phone for online classes. Another parent with three sons and one daughter who all attend the PiE program expressed that since they have one cell phone at home, only the older boys can take online classes. The youngest girl has been out of school for over a year.

Public vs. Private Educational Institutions

There are large disparities between state-funded and private educational institutions, in terms of both the accessibility and quality of the open and virtual programs and how they have responded to the pandemic. Throughout Nepal, this has been a major challenge for rural areas that lack the infrastructure to support a shift to online and distance learning. However, in interviews with SXC students and the PiE community, it is evident that these dynamics are also playing out to some extent within urban centers. In the Kathmandu Valley, varying policy trajectories and institutional responses are impacting low socioeconomic spaces and informal settlements. Students who lack the means to access online learning platforms and have low proficiency in English and technological skills are left behind. This public-private divide is visible within the SXC community, as middle-class students from SXC, a privately funded university, are supporting and teaching PiE students, who mainly come from public schools.

During spring 2021, Adwitia Grung, a SXC student who is a previous PiE trainee conducted research for a class paper on the impact of COVID-19 on public versus private schools in Kathmandu Valley. In her interviews with public school students, she found that state-funded institutions introduced a small tuition fee for classes, which created barriers for access to education among financially insecure families.

Students in government schools are supposed to get free education. But then what I found out is that the schools were asking for a certain amount of money. [It] was not really that much for us, that is middle class people, but then it was a lot for someone who did not have a proper job during lockdown and was having a hard time getting two meals per day. Two months to three months after the lockdown [the government school students] were supposed to be promoted to a senior class, but the student that I spoke with, she was not getting to take the online classes because her parents could not pay the money and she had three other younger siblings, and even they were not getting to study. It is only the students who paid [the] money who got to be promoted to the next class (interview with Adwitia Grung, PiE trainee, April 20, 2021).

The initial lockdown in March 2020 took place right before year-end exams. While all exams were postponed, there was a stark difference in the ability of private versus public schools to adopt digital platforms for remote examinations. In several private schools and universities, exams took place between one to four months after the lockdown began. In contrast, several public schools were left scrambling to respond to the challenges of distance and online learning. According to Nepal’s Education Department, only about 48% of public schools were online in the six months that followed the initial lockdown. Exams in many public schools were postponed beyond six months and in some cases canceled altogether.

A PiE trainee stated that students in public schools receive less support, even if they are able to access virtual programs—some do not attend classes, and others have missed an entire year of studies (interview with Adwitia Grung, PiE trainee, April 20, 2021). For many students, attending the PiE in-person classes between February 2021 and April 2021 was the only formal education they received during the pandemic. While the PiE program has been able to provide support to these communities, PiE is set up as a supplemental program to accompany and help students in their public education; it is not designed to fill major gaps in formal education for a sustained period.

Mental Health

The COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures have increased the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among communities in Kathmandu Valley. The second wave of the pandemic that hit in February 2021 has been a particularly tough test for Nepal. People are not only suffering from the health effects of the virus but are also struggling to manage the accompanying financial stress and strict social distancing. Across Nepal, limited health assistance, the lack of state safety nets for informal workers, and increased financial difficulties have made an overwhelming situation even worse for many households. In Kathmandu Valley, the psychological impact of the pandemic hits on all societal levels.

For students, feelings of isolation from peers, friends, and family—as well as uncertainty about education and exams—have impacted mental health. In the PiE community, one SXC trainee who spent five months in the program lost communication with everyone during the COVID-19 outbreak and started having increased anxiety about her future. Vipassana Chettri shared that “when COVID happened, I lost communication. I lost communication between my friends, and also started having anxiety attacks” (interview with Vipassana Chettri, PiE trainee, April 14, 2021). Belonging to a middle-class family, she was able to get access to professional mental health services and therapy sessions.

PiE students and other children in the settlement areas are facing even greater challenges, and many do not have the support or resources to deal with the challenges of the pandemic. On top of the financial crisis, youth in the settlement areas are missing out on education, activities, and interactions with friends as many have been out of school for over a year. Most of these students lack support from their schools. In comparing the experiences of privately and publicly educated students, it is apparent that the policies and responses of Nepali educational institutions have a significant impact on students’ development and mental health.

PiE Adaptations during COVID-19

The ability of SXC to quickly respond to pandemic conditions, including through mobilizing digital platforms for continued online classes and organizing a COVID-19 safe opening of in-person classes at the end of the first lockdown, significantly contributed to its ability to support the marginalized PiE students. Several SXC trainees and volunteers also took their own initiative to support the PiE students during the pandemic. One SXC trainee explains that “we wanted to do something [for the PiE students], but we did not know what to do to help. So, the most we could do is talk to the students via a phone call and then, you know, help them with preparation for several exams” (interview with Adwitia Grung, PiE trainee, April 20, 2021).

For the PiE program, reopening with COVID-19 safety measures meant that students from the settlements and those without access to digital education could attend classes. One PiE parent shared that she was very concerned about her children’s education after a year of online classes.

I was really worried about my kid’s education. And I am quite sad because the school and PiE have stopped the education and the studies, which was going smoothly before COVID-19. And also, my children get distracted easily when studying online classes, so I was really worried about it (interview with Chanchali Lama, PiE parent, April 27, 2021).

Many PiE students did not attend school due to public school closures, family financial hardships, and the inability to access digital education. A PiE trainee observed that there were a lot more students in the program after the first lockdown because they were not getting schooling elsewhere—PiE became their only source of education (interview with Vipassana Chettri, PiE trainee, April 14, 2021). This was partly because several public schools remained closed even when the lockdown was lifted at the beginning of 2021, and many students were not able to attend online classes. Previous PiE students also brought other children into the program. As a result, PiE enrollment increased to either 80 or 90 students during COVID-19, much higher than before the pandemic.

To address the increased number of students relying on PiE as their only form of education, the program adjusted its classes. While the program usually combines academics with growth-oriented self-development activities, during the pandemic, it shifted to focus more on academic and educational support, as many PiE students were not attending school.

After classes, PiE trainees held meetings together to discuss how to motivate their students and encourage them to study amid hardships at home. Due to the complex challenges of the pandemic, the PiE program was shut down during the second lockdown in April 2021. Although not officially directed by the program, several SXC students found ways to connect with PiE students by calling their families to check on them.

The Potential of Private-Public Partnerships in Education

The COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures are reinforcing social injustices and inequalities that threaten to reverse progress in building social inclusion, improving education indicators, and reducing poverty. Although many universities and schools in Kathmandu Valley have online learning platforms and offer virtual classes, the continuing pandemic means that marginalized students in the lowest income brackets are being left behind. At the time of publication, COVID-19 containment restrictions are still in place and only a small number of universities and schools in Kathmandu Valley have reopened. As the pandemic continues, the responses and support of educational institutions will be critical for mitigating the impact on students.

Students from the most marginalized communities and settlements in Kathmandu Valley have become increasingly reliant on community-engagement initiatives carried out by private universities and schools—including programs like PiE—for continued education during the lockdown. Through its local place-based approach, the PiE program has been able to respond to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and fill growing education gaps. By providing free support to students from the settlements and providing COVID-19 safe PiE in-person class

I think the PiE program has done a lot, especially in education and even in a way the [St. Xavier] university responded to the pandemic (interview with Vipassana Chettri, PiE trainee, April 14, 2021).

There are several opportunities for universities and schools to address some of the social justice issues facing students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. At this point, most schools and universities in Kathmandu Valley have established digital platforms for open and distance learning and teaching. Interviews with members of the PiE community highlighted several measures that could lessen the impact of the pandemic and increase the ability for marginalized students to continue their education for marginalized students:

- Increased effort to provide stipends, support data usage, or provide phones and computers to marginalized students through educational institutions and public-private partnerships was suggested by several parents of PiE students as a way to better address access issues (interviews, PiE parents, April 22, April 27, and April 28, 2021).

- Clear and regular communication with students regarding updates and adjustments in policy and practice was stated as a factor that may help relieve some of the pressure and anxiety students have been feeling during the lockdown. Students felt less anxious and more reassured about their future when they received regular communication and were reassured by their teachers (interviews, PiE trainees, April 20, 2021; interviews, previous PiE students, April 28, 2021).

- Student support platforms focused on mental health and psychological support for students—including formal school groups and informal student groups, direct and individual calls to students, as well as encouraging and facilitating student-to-student communication—may help to alleviate student stress (interviews, PiE trainees, April 14 and April 20, 2021; interview, previous PiE students, April 28, 2021).

- Setting up formal administration procedures and platforms to provide educational support and remote tutoring to marginalized students and their families during periods in which the in-class sessions are not possible, specifically for the PiE program. This is taking place informally, but as a result, only some of the PiE students are being reached (interview with previous PiE trainee, April 20, 2021).

While the key challenges and opportunities highlighted above do not represent the full breadth of responses and actions required to combat the extensive challenges of the pandemic and underlying issues, they provide important insight into the needs of students in Kathmandu Valley, expressed by the PiE community. Sharing the experiences of the PiE community and looking at the varying responses from private universities and public schools can be an important first step in identifying some best practices to increase support for students during the pandemic.

Endnotes

- The Plus Two program is the Nepali higher secondary program equivalent to high school Grades 11 and 12 in the U.S. education system. In Nepal, secondary education takes place in two stages. Grades 9 and 10 follow a common academic curriculum leading to a School Leaving Certificate. During Grades 11 and 12 there are opportunities to follow separate streams in commerce, education, humanities, or science, and to receive a higher education certificate. SXC offers a Plus Two science program with two sub-streams: biology and physics.

- The A-Levels are a subject-based qualification conferred as a part of the General Certificate of Education, as well as a school leaving qualification offered by the educational bodies in the United Kingdom. In Nepal, A-Levels are a popular choice as an alternative to the Plus Two program and National Examination Board . At SXC, A-Levels are affiliated with Cambridge International Examinations. The offered courses are accounting, biology, business, chemistry, computer science, economics, English general paper, mathematics, physics, psychology, and sociology.

- The term “settlement” refers to squatter settlements, also known as informal settlements or slums. A squatter settlement is defined as a residential area which has developed without legal claims to the land and/or permission from the concerned authorities to build; as a result of their illegal or semi-legal status, infrastructure and services are usually inadequate. In Nepal, rural-urban migration has resulted in the rapid growth of slums and squatter settlements in the Kathmandu Valley. Between 1985 and 2009, the number of squatter areas in Kathmandu increased from 19 to 40.

This report was authored by Tierra Hatfield (G’22). Rohil Kulkarni (SFS’21) contributed to conducting interviews.

Featured Person: Tierra Hatfield Person