Global Citizenship in Portugal

By: Vikki Hengelbrok (C'23)

November 28, 2025

This project examines the core principles of Fundação Gonçalo da Silveira (FGS) in Lisbon, Portugal and the sociopolitical landscape of the country. This NGO was founded in 2004 and is one of many organizations that contributes to the network of the Society of Jesus in Portugal.

Exploring the Core Principles of the Fundação Gonçalo da Silveira

Located in the northern part of Lisbon, the Fundação Gonçalo da Silveira (FGS) sits on the second floor of a building that acts as a communal space for students at the neighboring Jesuit university. They are one of the few groups that occupy the complex that together create a nucleus of religious teaching, thinking, and gathering. Their open office design is tangible evidence of their ethos of collaboration. As I was introduced to FGS team members and colleagues within the building, I was immediately comforted by their kindness and warm welcome.

Figure 1: The courtyard of FGS’s office with a large tree and motorcycle parked underneath. The yellow building on the left is where their office is located, among other Jesuit works in this complex. (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

Founded in 2004, FGS is one of many organizations that contribute to the network of the Society of Jesus in Portugal. Settling in the Iberian peninsula in the sixteenth century upon the request of King John III, the Society of Jesus founded numerous schools and higher education institutions. These educational bases were recognized for their rigorous curriculums, both religious and secular, and are known today for having an instrumental impact on the Portuguese education system. FGS’s ties to the Catholic Church are instrumental to its work. This connection does not exclude nor define the partnerships that FGS pursues. Rather, FGS’s relationship with the Society of Jesus at its founding played an integral role in shaping the organization's fundamental values and continues to impact its ways of proceeding.

Initially, their projects were devoted to transforming the educational landscape through missionary trips to other countries. Their projects have since shifted toward addressing issues closer to home. They have adopted five principles for generating change within their communities.

The Five Principles of FGS:

- School as a space for social justice transformation

- Dialogue between civil society and higher education

- The link between ecology and social and justice transformation

- The link between a global vision and local practices

- Connection between different territories

In the summer of 2022, I spent three weeks in Lisbon, Portugal, where I explored the interplay of FGS’s core principles within the sociopolitical landscape of the country. To do so, I conducted 21 semi-structured interviews with FGS team members as well as Portuguese teachers, partners, activists, and Jesuits who are close associates of the foundation. Aside from these interviews, I collected additional data through my participation in events where I gained firsthand experience with the inner and outer workings of FGS. Throughout my fieldwork, I traveled to four cities in Portugal, attended workshops at three universities across the county, participated in a conference among various Jesuit organizations and leaders in Portugal, and sat in on FGS team meetings, with the goal of immersing myself in the FGS world as much as I could.

Figure 2: Points on a map of Portugal representing the locations where the author accompanied FGS team members on trips to Portuguese universities where they conducted workshops, including, from north to south: Porto, Viseu, Santarem, Lisbon, and Beja. (Source: Google Maps, edited by Vikki Hengelbrok)

Principle 1: School as a Space for Social Justice Transformation

The concept of “global citizenship” is central to the FGS approach to fostering social justice in Portugal. The mission of FGS is “to fight inequality and social injustice through the development of a concept of Global Citizenship which promotes the common good, and contributes towards change in situations that generate poverty at local and global levels.” In partnership with schools, Portuguese higher education institutions, other civil society organizations, governmental bodies, and local communities, FGS mobilizes individuals from a variety of backgrounds to reflect on and address the injustices present in their local environment and globally.

Pope Francis’ publication of Laudato Si' reaffirmed FGS's mission as it further reinforced the concepts and projects that they pursue and also communicated the importance of this work to communities. In Laudato Si', Pope Francis advocates for greater care for our common home, saying: “We need to strengthen the conviction that we are one single human family. There are no frontiers or barriers, political or social, behind which we can hide, still, less is there room for the globalization of indifference.” This facet of indifference is one that FGS directly aims to address, through the promotion of the formation of a global citizen—one who is able to recognize their role and responsibility, locally and globally, in the inequalities around them.

The long-standing mission of FGS to use educational institutions as a space for social justice transformation was strengthened in 2016, when Portugal released the National Strategy for Citizenship Education. This new policy integrated global education concepts into school curriculums. It aims to implement a three-dimensional footprint on the student’s civic engagement, and interpersonal, social, and intercultural relations. This strategy set the stage for NGOs to pursue global citizenship projects within schools in Portugal, opening the door for organizations, such as FGS, to develop their important work.

Portugal’s current social and political climate continues to be shaped by the 48-year-long authoritarian government that ruled the country for the majority of the twentieth century. Between 1926 and 1974, censorship was a vital pillar of the authoritarian regime. The Salazarist government banned all forms of media in continental Portugal and its colonial territories from discussing a variety of subjects including racial integration, self-determination, elections, as well as social issues and public policies. These restrictions on freedom of speech effectively diminished public forms of political dissent, weakening the movements for change in the fabric of Portuguese culture for many years to come. At the same time, there was a rising movement that called for the independence of Portuguese colonies. Upon the fall of the authoritarian regime, the role of non-governmental actors in pushing projects that target education in the former colonies grew exponentially. This planted a seed for a culture that would become dependent on community action. While it wasn’t coined a term at the time, this was the beginning of Portugal’s development cooperation initiatives, and through collaboration with like-minded change-makers, the transition to global citizenship, the concept used today, materialized.

Figure 3: A viewpoint overlooking the center of the city of Lisbon. Sat atop a hill is the Castelo de São Jorge, with blue skies and the sea pictured on the right. (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok)

In the Portuguese context, global citizenship education entails dealing with the harsh realities of the country’s history under authoritarian rule and its problematic role as a colonizing nation. Having lived under the longest dictatorship of the twentieth century, the Portuguese have been conditioned and accustomed to accepting authority, making acts of protest uncommon, even at the most minor scale; contradicting a colleague for example, would be considered unusual. There is an emphasis on hierarchical relationships, where people tend to follow the rules, accept the norms of behavior, and depend on laws to enforce etiquette. One of FGS’s partners described this relationship to me, saying that, “Although the state is weak, it has a very important symbolic role.”

Reflecting the lasting silencing effect of censorship under the Salazar regime, Portuguese students are hesitant to participate in class discussions about political or social issues. Additionally, Portuguese students' admittance to university is directly associated with their performance on national examinations. The national curriculum and traditional classroom models emphasize the skills and knowledge required to perform well on standardized assessments. Thus, students prefer to focus on preparing for the national exams that are critical to their university acceptance (interview with Carlota Quintão, partner of FGS, June 9, 2022).

FGS’s global citizenship education programs contribute to a national effort to reimagine the country’s education system. Their projects, such as escolas transformadoras, aim to break down the standard classroom model by partnering with higher education institutions across Portugal to create room for critical reflection and social transformation. Making spaces where students' and teachers’ voices are heard by the administration is one small way that some higher education institutions in Portugal are implementing this into practice. On a larger scale, FGS’s project Sinergias administers a matchmaking process that facilitates dialogue and partnerships between civil society organizations and universities. Hence, they are able to collaborate in research, training, and events.

There are some studies that say that kids in Portugal do not like to go to school at a higher rate than it was 15 years ago. Somehow, we are not preparing kids for the future. They will have challenges. They will have to face climate change, to face a more fractured society. But we are preparing them just to do an SAT, to finish high school just to go to college. So, you're not giving them existential perspectives that can help them build bridges between now and in the future (interview with Sara Borges, project manager at FGS, May 24, 2022).

However, FGS’s efforts to introduce a new education model have been met with opposition. Families of current students wish to adhere to conventional educational styles, claiming that the experiential type of learning “doesn't belong with schools. They belong to the families,” and the school has the responsibility of teaching “technical knowledge” (interview with Hugo Marques, project manager at FGS, May 26, 2022). Additionally, FGS staff shared that many educators are not comfortable with the global citizenship model of education. Global citizenship promotes a critical thinking process where students are encouraged to question, criticize, and dismantle the norms. This model of education seems counterintuitive to parents, faculty, and often students.

Principle 2: Dialogue Between Civil Society and Higher Education

Through my interviews and observations, I quickly came to realize that integral to the FGS process is its focus on collaborative models and emphasis on the process over the outcome, both internally and externally. The collaborative approach used by the FGS team internally is adapted to help bridge the existing divide between civil society organizations and higher education institutions.

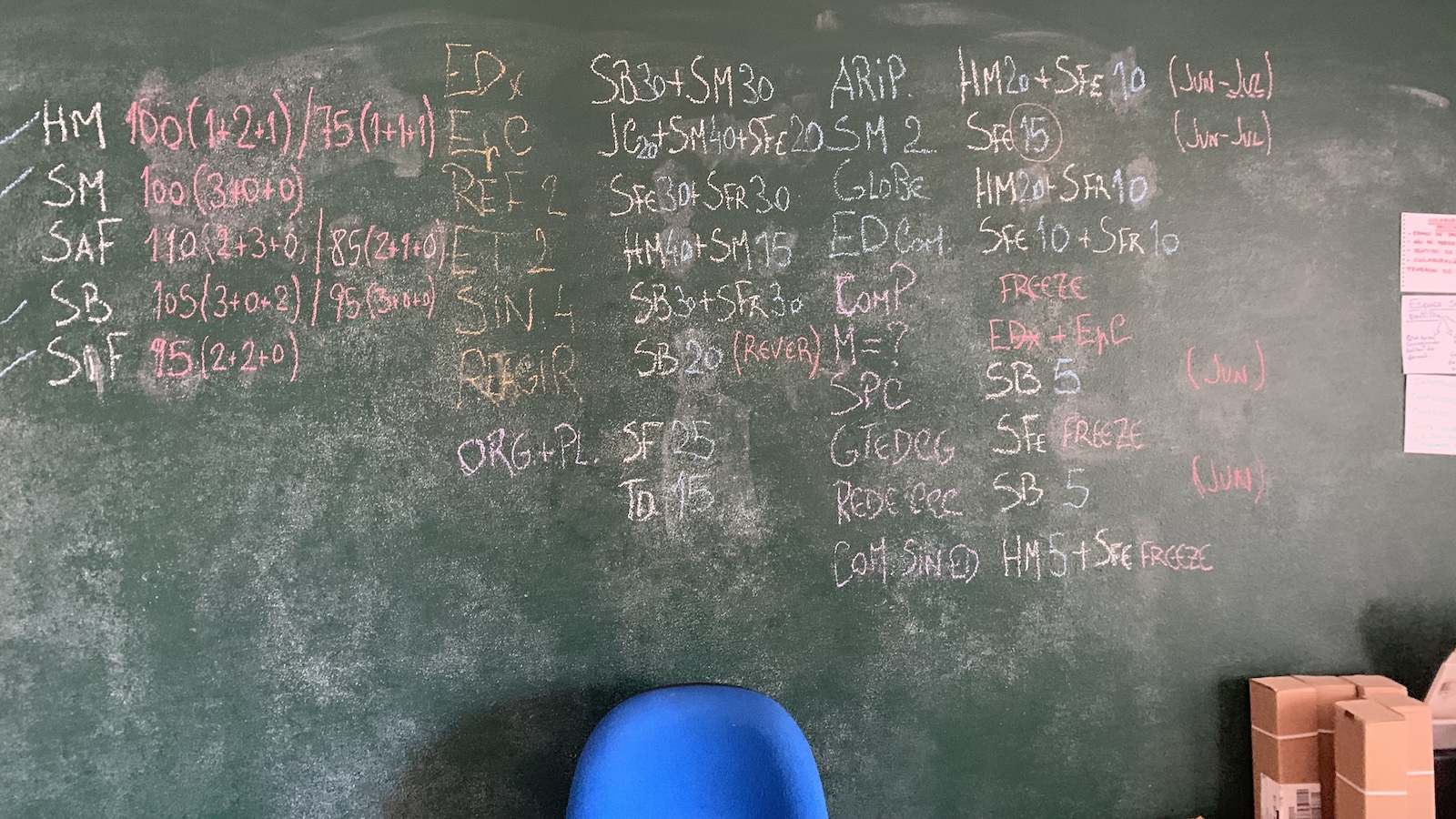

Cooperation runs like a thread through the institutional culture, evident in the ways FGS prioritizes partnerships, designs projects, and even their office spaces aim to foster an environment of sharing. People do not have individual rooms, but rather sit near one another and can easily ask questions, or consult coworkers for advice. No one works alone at FGS; everyone follows a paired-project model, and at least two FGS team members are always partnered to lead a project in order to “deepen the thoughts about all the areas that [they] are working” (interview with Sandra Fernandes, project manager at FGS, May 30, 2022). This practice cultivates an environment where critical feedback is welcomed, new ideas are appreciated, and dialogue is constant. FGS community culture appears even through the grounds where they are located; inhabiting the second floor of a building in the north of Lisbon, FGS is one of the many Jesuit organizations in the complex.

Team meetings are held monthly to update their partners on projects and create an atmosphere where they can discuss, deliberate, and debate the best methods for achieving their goals. This prioritization of collaboration has roots in the Jesuit practice of discernment, a principle of decision-making that emphasizes the benefits of taking time to ponder one’s choices. Teresa, the president of FGS, described to me how discernment takes shape in FGS processes. For example, when someone brings a new project idea or issue they “talk, okay, this, we must take into account, and then, we decide, not in the moment, but one to three days after,” (interview with Teresa Paiva Couceiro, executive director of FGS, June 6, 2022). They allot a significant period for people to come to conclusions and discuss their ideas together. While time is a luxury, especially in circumstances in response to an urgent crisis, FGS aims to devote sufficient energy to its decision-making.

This internal collaboration is mirrored in external partnerships FGS holds with local communities, organizations, institutions, and governmental agencies, in that they value the opinions and perspectives of everyone with whom they work, and make sure that they contribute to the process and facilitate a learning environment.

Figure 4: An FGS workshop held at the Instituto Politécnico de Beja (IPBeja), part of their Escolas Transformadoras initiative. University teachers and administrators sit in a semi-circle, facing the projector, and one of the leaders of the workshop. (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

One of their most renowned projects, Sinergias, takes dialogue headfirst by nurturing the relationship between higher education institutions and civil society organizations, in order to strengthen development education training and encourage the dissemination of knowledge. The ingredients of “flexibility, coherency, a sense of purpose” are what make FGS work compelling to stakeholders, its mission to learn from others, and “systematize new ways” attracts experimental thinkers and prompts innovative ideas (interview with Susane Constante Pereira, partner of FGS, June 2, 2022).

FGS team members prioritize close relationships with their partners; many of my interviewees had known FGS colleagues for years on personal and professional levels. Every workshop had incorporated time for an informal lunch to be held, where the topic of the project was rarely discussed, but rather, people got to know those who were unfamiliar or caught up with those they had known for years. Often, peoples’ children were at these lunches, and I quickly realized that the relationships outside of the professional sphere were a vital ingredient to how FGS does what it does. As an outsider to FGS, I experienced this FGS phenomenon of creating a family with those in their community. I was immediately welcomed, not as an external researcher, but as a member of the team. By developing these relationships, and by subsequently establishing mutual trust among actors, transparency is more likely, and, as a result, the critical approach that FGS works so hard to incorporate is significantly more effective. Innovation cannot exist without new ideas, and new ideas demand an environment that welcomes critique, as much as support.

It is very rare to find a partner who is so welcoming and so joyful and easygoing. And that doesn’t mean you lower your standards in terms of quality. It just means you’ll meet people in the middle, and you’ll find ways to connect within the differences (interview with Filipe Martins, partner of FGS, June 8, 2022).

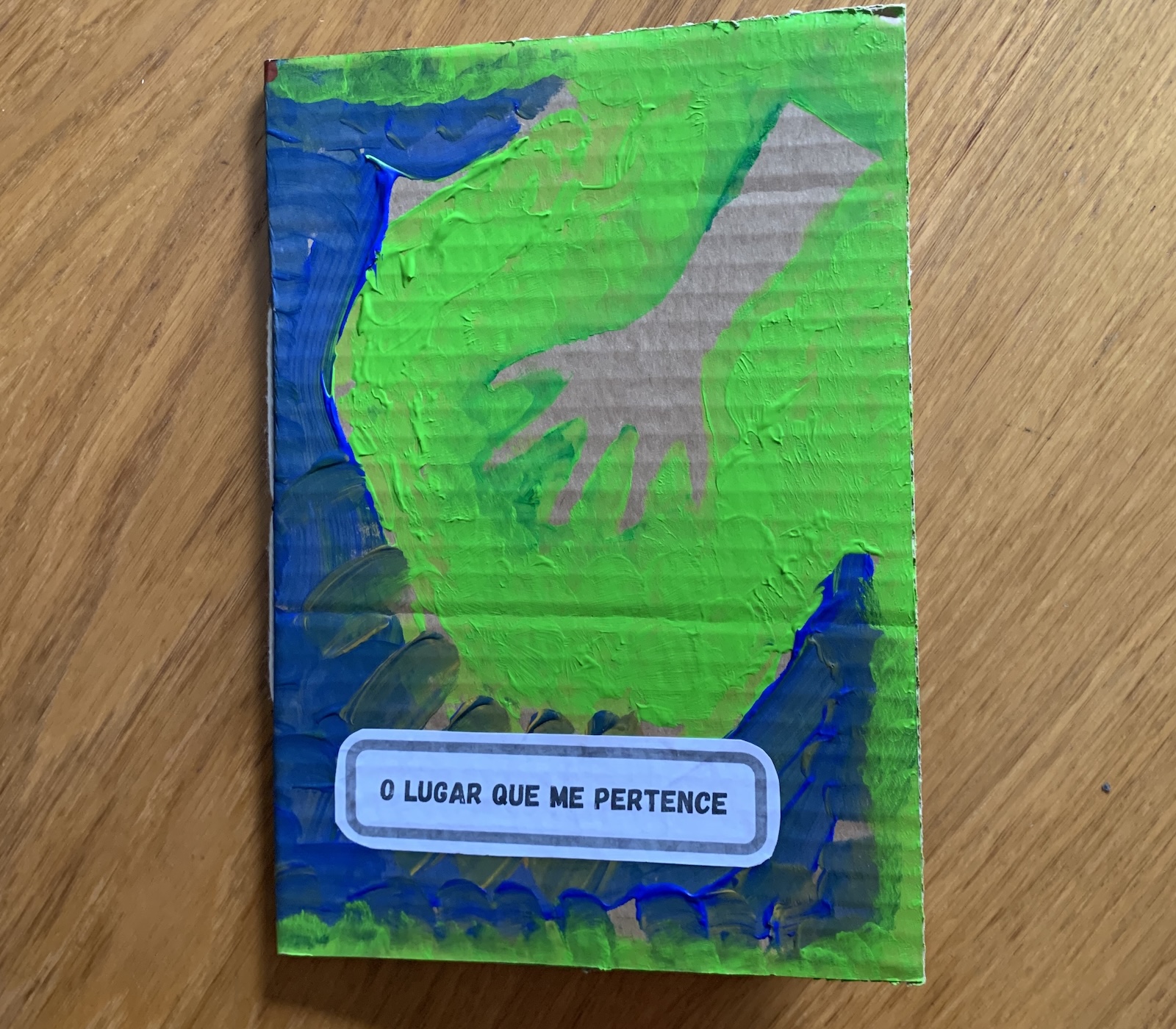

Figure 5: The Brazilian initiative to use recyclable materials to create hand-crafted and painted books. This particular book is painted in green and blue, with a handprint reaching from the right. Underneath, it reads: “O Lugar que me pertence” or “The place that belongs to me. ” (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

One project that exemplifies this mission is through Cartoneros books. This workshop is a reflective and pedagogical tool that aims to prompt questions of eco-dependency and encourage the participation of people and communities who traditionally have been excluded from literate cultures. This initiative began in Argentina, has since spread across Latin America, and now has come to FGS in Portugal, where you recycle used pieces of cardboard and transform it into a book cover, where anyone is able to fill in the pages inside. Sara Borges, a team member at FGS, told me how, when they bring this workshop to schools, students and teachers are often intrigued about the idea of decorating their own cover, and by the end, through the creation of their own stories, come to understand their relation to sustainability and ecology (interview with Sara Borges, project manager at FGS, May 24, 2022).

Maria's cartonera book - Dulcinéia Catadora, Brazil. The video explores the Cartoneros movement, which originated in Argentina in 2003 and has extended its influence to various countries across Latin America, Europe, and Africa. The clip features Maria Aparecida Dias da Costa from Dulcinéia Catadora in São Paulo, Brazil, demonstrating the process of crafting a cartonero book from start to finish.

Figure 6: Hugo Marques, a project manager at FGS, smiles at the camera while sitting on a couch with paintings hung on the wall behind him (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

The concept of global citizenship is at the core of FGS’s mission. Sandra Fernandes, a project manager at FGS, describes global citizenship education as “a way of see[ing] our society, our own lives with a critical perspective, with a concern of linking the local level and the global level and being able to see how things are interconnected and how my actions, not just individually but as a society, have consequences in other places.” (interview with Sandra Fernandes, May 30, 2022)

The following paragraph is a simplified exercise of a simulation that took place during an FGS team meeting in which I participated that exemplifies how FGS defines global citizenship:

Imagine that you are standing by a river, and all of a sudden, you see that there are children in the water who are drowning, and the current is getting stronger. What is your first impulse? Then, you look up the river and realize a fleet of boats all seem to be throwing children into the water. This number is multiplying the longer you stand there. What do you do now? Do you help the kids close to you? Do you swim towards the boats? Can anything be done?

This simulation was created by Vanessa Andreotti, a Brazilian educator and researcher of global citizenship, to examine how we problem-solve and aims to represent circumstances where one must choose to devote resources to the issue in front of you or towards addressing the root of the issue. She argues that education is the pathway to facilitating this type of critical thinking: You could decide to help individual children or go up the river to the villages where the boat crew came from and stop more boats from leaving. The latter choice is one supported by a global citizenship mindset, a concept that FGS diligently promotes and fosters within Portuguese schools. As described by one FGS employee, in every manner, global citizenship aims to bring in “this critical thinking and acting, to get in touch with the interconnectivity in the world” (interview with Hugo Marques, project manager at FGS, May 26, 2022).

Principle 5: Connection Between Different Territories

Amor à Camisola: A Love to Your Shirt

The phrase amor à camisola was introduced to me at a conference I attended with FGS, where various Portuguese Jesuit works came together to reflect, debate, and share their insights on the concept of sinodalidade, or synodality. Synodality refers to the participatory, inclusive approach to decision-making within the church. During one of the discussions at this conference, the phrase amor à camisola was presented on the screen, and various people spoke about their take on this Portuguese expression. The reactions varied from positive and negative, piquing my curiosity to learn more about this controversial ideal.

Amor à camisola is a Portuguese phrase whose literal translation is “love to your shirt,” and it represents a dedication to, sacrifice for, and honor towards your work. This passion transcends the binds of occupation, what you do is your purpose, one which you wear with pride. Who you work with and what you work for is your identity, and instills a sense of belonging and purpose. This phrase is viewed predominately in a positive light and is an integral part of Portuguese culture, where people with a strong sensation of amor à camisola “work much more than they should work, from nine to five on Monday to Friday,” (interview with Laura Dewitte, partner of FGS, May 30, 2022). Especially in the field of social transformation or education, the activist identity of this professional role seeps into every aspect of one’s daily life. Portugal itself is a very community-driven culture, where people depend on the work of grassroots organizations, or the people themselves, to enact change or provide support. The fact that the phrase amor à camisola is unique to the European Portuguese language alone illustrates the distinctive type of work ethic that their culture has.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) in Portugal are organized based on their respective objectives. Many of the challenges faced by Portuguese nonprofits stem from the funding models that emphasize short-term timelines, and as a result, short-term results. In comparison to other European countries which adopt longer funding cycles, most projects at civil society organizations are working with a two to three year deadline. This much shorter perspective diminishes the capacity of these programs and the organizations that manage them. There is a smaller “perspective of continuity,” that contradicts the fundamental nature of many of the projects that FGS leads, which is to instill long-term change. From an organizational lens, Susane Constante Pereira, a partner of FGS, described to me how “you are permanently in a kind of survival mode,” becoming hostage to the system and its various restrictions (interview with Susane Constante Pereira, partner of FGS, June 2, 2022).

'Amor à camisola.' Well, it means that you really value what you are doing. You really believe that what you are doing is essential to change things. It's the core of all that you do, (Interview with Sandra Fernandes, project manager at FGS, May 30, 2022).

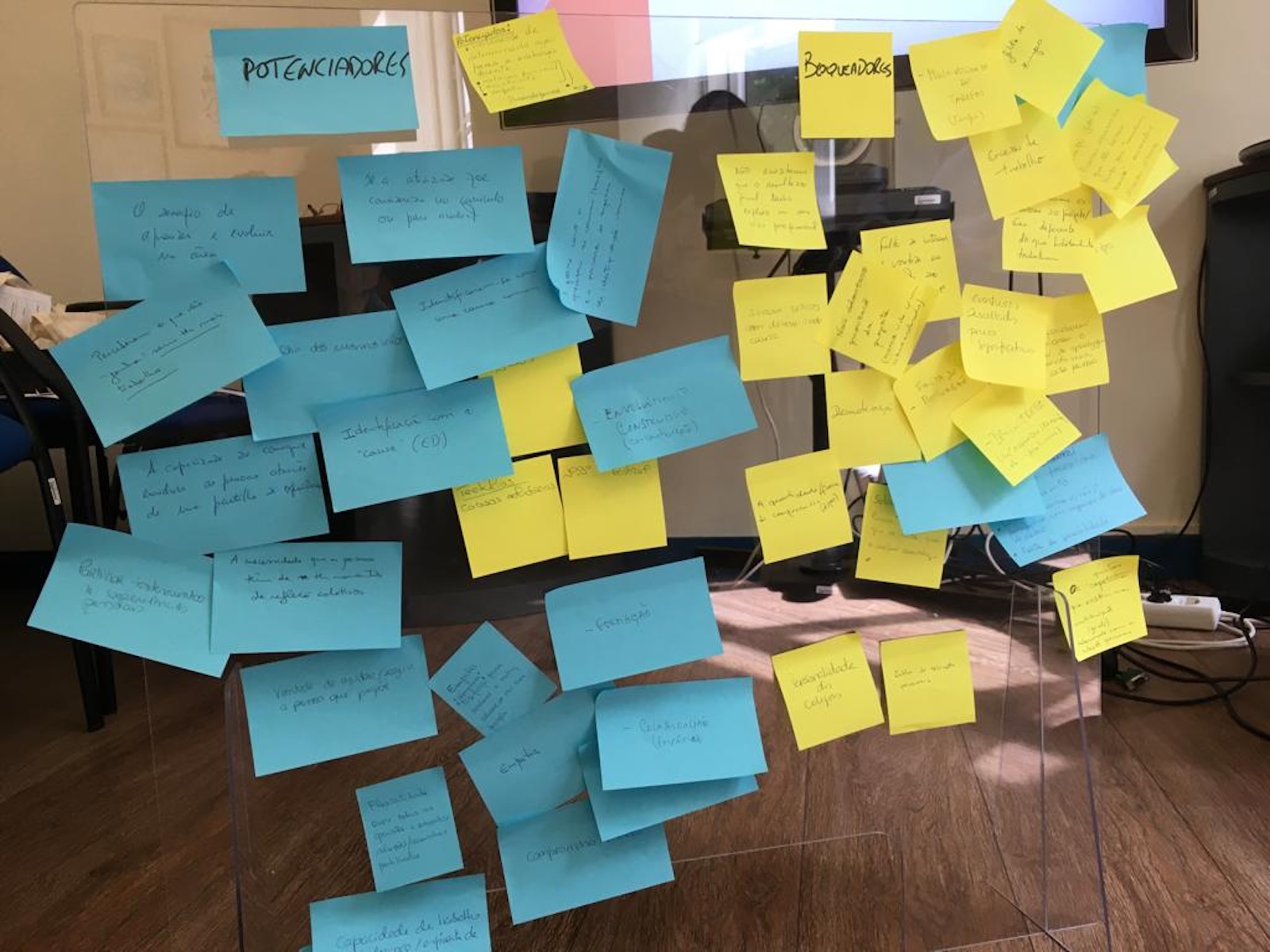

Figure 7: An FGS group exercise for teachers at higher education institutions to brainstorm the “potenciadores”(stimulators) and “bloqueadores” (inhibitors) (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

The COVID-19 pandemic presented an array of new challenges: limiting the ways people came together, constricting the budgets for non-profit organizations, while demanding more activism and community work of these same organizations. An overarching tension appears, where these institutions are considered “non-governmental” and therefore not affiliated with executive powers, yet, they are dependent on the government for a majority of their funding. In comparison to Spain, where the government views the civil society sector as a partner, the Portuguese government’s lack of support only perpetuates the weakness of their voice, whereas “if the government were afraid of us, they would give us much more money” (interview with Teresa Paiva Couceiro, executive director of FGS, June 6, 2022). FGS has an interesting position: they have been recognized through their prior collaborations with the Ministry of Education to develop the National Strategy on Citizenship Education to be a valuable organization, and therefore have a stronger input than others. However, they too are afflicted by limited funding cycles, which must be interrupted in order for non-profits in Portugal to reach their full potential, and for their projects to encourage long-term outcomes.

I think when you are working on something that you cherish, something that you feel is part of you, you create that amor à camisola. And sometimes, you have to work on weekends. Sometimes, you have to work overnight. Sometimes, you can follow your schedule. But more than that, I think the value is because you really devote yourself to the moment and to what you are doing (interview with Sílvia Franco, project manager at FGS, June 8, 2022).

The ideal of amor à camisola is often a deceptive double-edged sword. Many people, most of whom work in the social justice or education fields, that I spoke with felt that they were overburdened, overwhelmed, and under-compensated for their work. For teachers, as well, “the educational system in Portugal, it's a very compressed system when teachers do not want to be teachers because your career is so full,” (interview with Sara Borges, project manager at FGS, May 24, 2022). Burnout takes hold over many, leading to turnover across these fields. The pandemic only exacerbated these conditions. It blurred the line between home and work, making this “love to the shirt” inescapable.

“What I feel with the people, after the pandemic, where people had that sense of amor à camisola, that they are really tired, and they are not able to continue this work. I’m not talking about FGS specifically; I'm talking about people I know that work in [the civil society] area, (anonymous interview, May 30, 2022).

In terms of the social transformation achieved through their projects, FGS team members clarify that they prioritize the process over the outcome. Oftentimes, the lessons come about over the course of their project and may not be realized for years to come. They believe in a long-term approach, where the results of their efforts take years to materialize. This can be challenging for funding purposes, especially considering that the funding models in the non-profit sector in Portugal are shrinking to become focused on short-term goals. This process-oriented thinking goes against traditional mechanisms in Portugal, and not everyone can grasp the often intangible transformations that come about as a result of FGS’s efforts.

La Salete, a partner of FGS, describes how as children we constantly question the norms and rules in our surroundings, but as we grow up, “we are taught to leave that question out,” (interview with La Salete Coelho, partner of FGS, June 3, 2022). She finds that teaching global citizenship aims to reignite this curiosity and critical perspective. These principles may be the key to broadening the scope of education, inspiring younger generations to participate in their communities, and fostering future adults of society to be more conscious, understanding, and receptive to their relation to the spaces they occupy.

Figure 8: Inside their group meeting room, four of the FGS team members stand alongside the author on her last day in the office. From left to right: Sandra Machado, Teresa Paiva Couceiro, Vikki Hengelbrok, Sílvia Franco and Sandra Fernandes. Teresa holds a bottle of Portuguese port and the author holds a cartonero that she had just made. (Source: Vikki Hengelbrok's personal photos)

I would like to see society and the world functioning where you put people before everything else, before profit, before goods, before money, and people must be in front. I feel that, through education, you can fight for this to be a reality. I don't know if it's in the near future or a further one, but I really hope that we steer the ship to start thinking about people and about communities (interview with Sandra Machado, team member of FGS, June 6, 2022).

Sandra’s vision–in harmony with FGS’s mission– proposes a world where the well-being of others, the collective human experience, the preservation of communities, and the nurturing of empathy and compassion take precedence over material commodities. While the path to this dream may be unclear, FGS has, for 10 years, acted as a catalyst for commotion, conversation, and change within their communities to make this vision a reality. Achieving this has been no easy feat: working within a culture rooted in complacency that is also driven by community action; a resonant clash between their innovative ideas and the fear of diverging from tradition; valuing hard work within a system that fails to provide sufficient support. These dichotomies are ones that FGS is tasked to navigate through, in order to achieve its mission of creating global citizens.

It does so by consistently putting people first, committing to collaboration, mutual respect, and critical forward-thinking, and working diligently to broaden the scope of what we traditionally imagine "education" to look like. By implementing global citizenship within school systems, future generations will be instilled with the critical thinking skills required to contend with the injustices, conflicts, and crises to come.

The views expressed in this student research are those of the author(s) and not of the Berkley Center or Georgetown University.