Building Bridges, Not Walls: The Vision Behind the John Paul II Youth Center

By: Minahil Mahmud (SFS'26)

September 19, 2025

This research examines the John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center’s interreligious youth programming, the role of faith-based institutions in peacebuilding, and how the center seeks to be a sign of hope for post-war reconciliation in Bosnia.

The John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center: Education and Peacebuilding

The John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center (Nadbiskupijski centar za pastoral mladih Ivan Pavao II) in Sarajevo, established in 2007 under the leadership of Dr. Rev. Šimo Maršić, serves as a vital hub for youth development in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Founded on the principles of spirituality, encounter, and education, the center annually engages approximately 10,000 young people from across Bosnia through diverse programming. These initiatives span volunteerism, youth activism, interreligious dialogue, addiction prevention, democratic awareness, environmental protection, and support for marginalized youth. The center’s mission was particularly shaped by Pope Francis’s 2015 visit, during which his call to “build bridges, not walls” became a guiding principle for the organization's work.

Figure 1: A large crowd gathers indoors, excitedly reaching out and taking photos as Pope Francis, dressed in white robes and a cross necklace, walks through the crowd. Surrounded by security personnel and clergy, he smiles and interacts warmly with people lining the path. The atmosphere is energetic and joyful, with many people capturing the moment on their phones. (Source: John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center website)

The center’s flagship interreligious program, Let’s Step Forward Together, launched in 2013, exemplifies this bridge-building mission. The program brings together high school students aged 14–19 from various religious backgrounds and regions across Bosnia for a week-long session. The program’s structure uniquely relies on peer educators, often former participants, who undergo specific training to lead subsequent cohorts. Participants engage in a comprehensive range of activities, including peacebuilding workshops, visits to different places of worship, sports, creative arts, and religious-themed dinners. As Center Director Rev. Šimo explained in his interview with me, while the center has Catholic roots, it actively creates space for all faiths, recognizing the need to address persistent ethno-religious divisions in post-war Bosnia.

We are starting from this place, as a Catholic place, but everyone is welcomed and we are trying to bring those who find in their religion reason for tolerance, for living together, for respecting each other. We cannot pretend that people are living peacefully and everything is okay, when we see that there are prejudices and there are people who do not want to enter into contact with the others, (interview, June 22, 2024).

In a similar vein, one of the program coordinators, Amina, described the goal of the program to me as “meeting… that young people have the opportunity to meet each other, sharing their experiences about their traditions, families, their community, not just speak about war and hate,” (interview, June 22, 2024). Therefore, according to the leadership of the program, Bosnian youth need a program that brings them together and offers a way around the ethno-religious divisions that dominate public and private life.

16. rođendan Nadbiskupijskog centra za pastoral mladih "Ivan Pavao II.". Video 1: The celebration of the sixteenth anniversary of the Youth Center in 2023, attended by students, peer educators, staff, religious leaders, and community members. The event featured a service at a church, musical performances, recitals, and games. (Source: The John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center YouTube channel)

Jerusalem of Europe: Faith, War, and the Wounds of Bosnia's Past

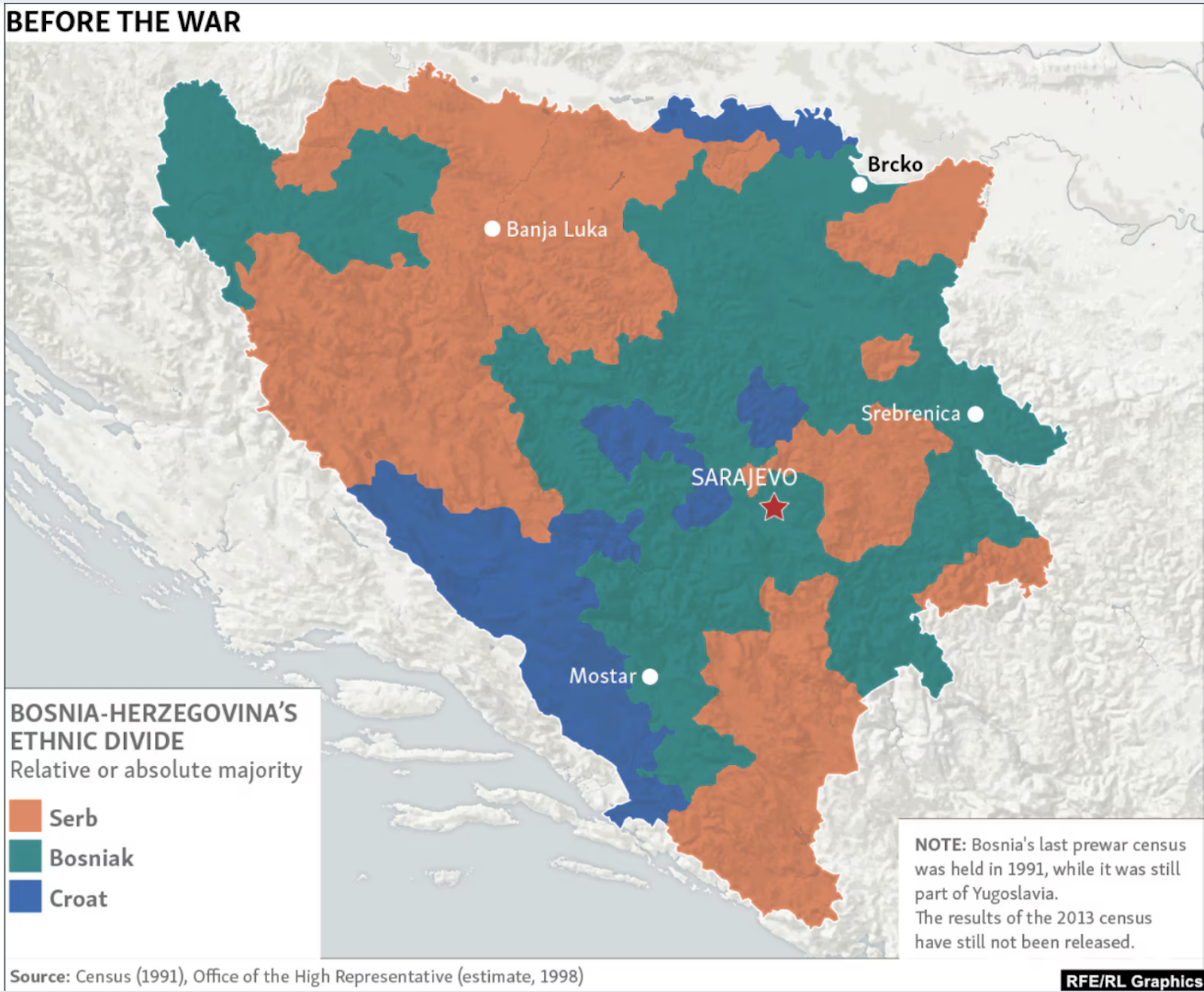

Many people I encountered described Sarajevo as the Jerusalem of Europe due to its rich history and religious diversity, offering invaluable lessons to the rest of the world in healing from conflict because of its own deeply troubled past. There are three major ethno-religious groups in Bosnia: Muslim Bosniaks, Catholic Christian Croats, and Orthodox Christian Serbs. There is a strong correlation between ethnicity and religion in Bosnia. In other words, people’s religious and ethnic identities are almost always synonymous and interchangeable.

Figure 2: A map of Bosnia and Herzegovina illustrates the country’s ethnic composition before the Bosnian War (1992–1995). This map, based on the 1991 census, shows Serb (orange), Bosniak (green), and Croat (blue) majorities interspersed throughout the country, with significant mixing around cities such as Sarajevo, Mostar, Banja Luka, Brčko, and Srebrenica. (Source: Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty “Bosnia’s Ethnic Divisions, Before And After Dayton”)

Figure 3: A map of Bosnia and Herzegovina illustrated the country’s ethnic composition after the Bosnian War (1992–1995). This map, reflecting post-war realities under the 1995 Dayton Peace Agreement, shows Bosnia divided into two main entities: Republika Srpska (orange, Serb-majority) in the north and east and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (green and blue, Bosniak- and Croat-majority) in the center and west of the country, separated by a dotted inter-entity boundary. The Brčko District (brown) in the northeast appears as a neutral, self-governing zone. Together, the maps above highlight how the war and subsequent political settlements solidified ethnic divisions. (Source: Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty “Bosnia’s Ethnic Divisions, Before And After Dayton”)

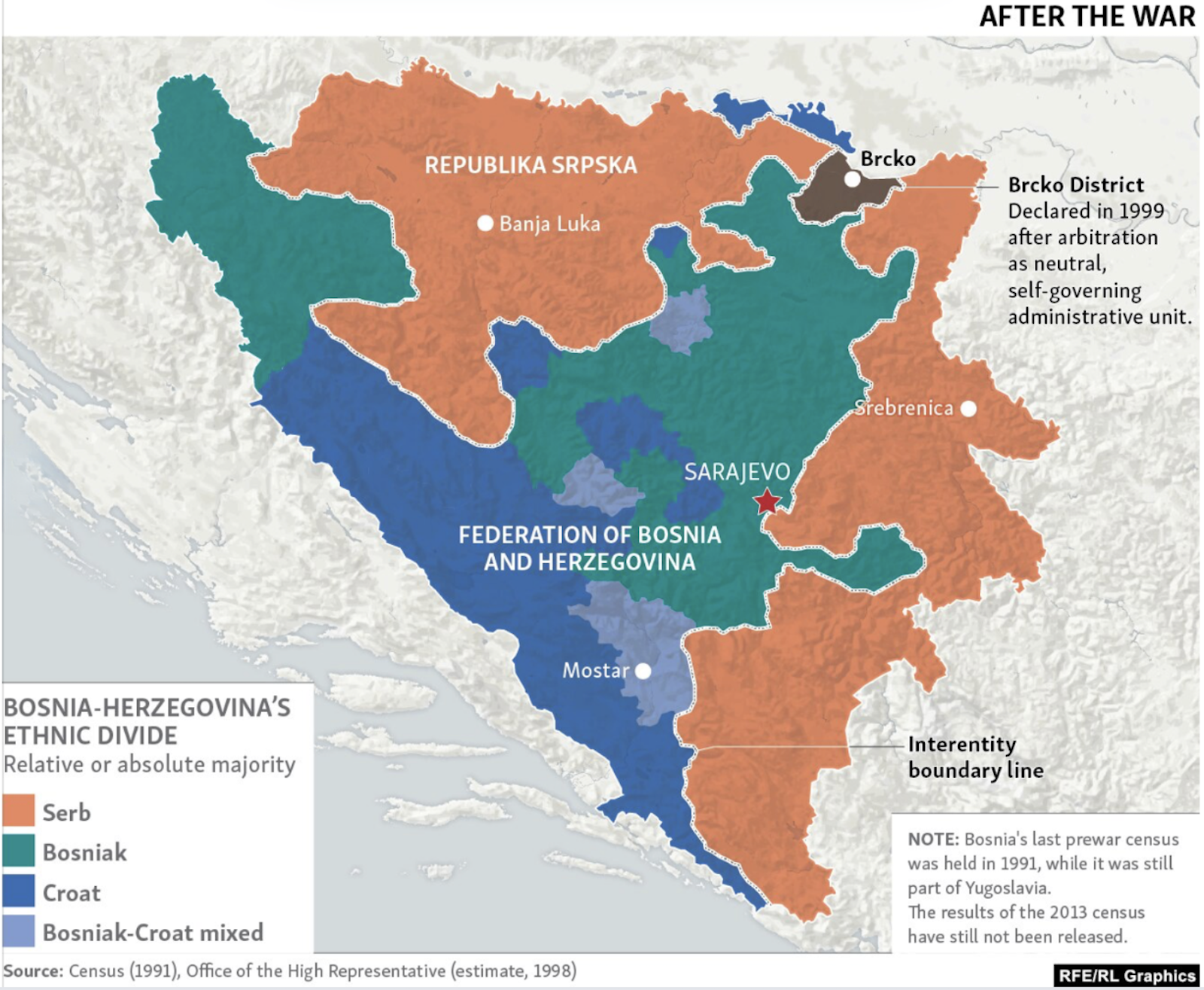

These divisions erupted in conflict from 1992 to 1995, when the country was torn apart by war. Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s, which gave rise to the independent states of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia, ethnic Serbs—who opposed the breakup of Serb-dominated Yugoslavia—launched armed struggles to establish separate Serb-controlled territories. As the conflict escalated, ethnic cleansing was perpetrated, primarily by Serb forces, and to a lesser extent by Croat and Bosniak forces who also engaged in fighting over territorial control. The violence culminated in the Srebrenica genocide, when Serb forces captured the city and systematically murdered more than 8,000 Muslim men and boys between July 11 and July 22, 1995.

My fieldwork in Sarajevo coincided with the twenty-ninth anniversary of this genocide, providing a sobering reminder of how recent these wounds are in Bosnia’s collective memory.

The Dayton Accords, also known as the Dayton Peace Agreement, were signed in 1995, bringing an end to the Bosnian War. While intended only as a temporary peace agreement, the Accords have served as the country’s de facto constitution to this day. The post-war solution of dividing Bosnia into two autonomous entities—the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska—has created enduring challenges. The political partition has institutionalized ethnic divisions within the country’s governance structure, complicating efforts at national unity and reconciliation in the decades since.

Figure 4: A dimly lit memorial room in the Gallery 11/07/95, a memorial art gallery in Sarajevo. The walls are covered in rows of black-and-white portrait photographs, honoring the faces of many individuals, all victims of the Srebrenica genocide. A simple wooden bench sits in the center of the wooden floor, inviting quiet reflection. (Source: Minahil Mahmud personal photos)

Figure 5: A street view in Sarajevo, showing a mural on the side of a building that reads "Remembering Srebrenica" above a large white flower with green center petals. The mural commemorates the 1995 Srebrenica genocide. Below it is a storefront. (Source: Minahil Mahmud personal photos)

In a society where religious traditions run deep, faith remains central to the lives of most citizens. Religious communities and institutions are thus uniquely positioned to facilitate reconciliation, a mission that will undoubtedly remain critical in the years to come. It is against this complex backdrop of historical trauma and persistent divisions that the John Paul II Youth Center has been operating since 2007 as a Catholic faith-based organization, working to build bridges across deeply entrenched ethnic and religious boundaries.

Where Dialogue is Lived, Segregation is Confronted, and Youth Lead: Social Justice in Practice at the John Paul II Youth Center

Experientially Living Interreligious Dialogue

During my fieldwork, a central question emerged: given Bosnia’s recent history of war and division, how would young people engage with each other through an interreligious program? What I discovered was compelling—the participants of Let’s Step Forward Together were not just learning about interreligious dialogue; they were experientially living it.

The program created an environment where participants naturally formed friendships that transcended the typical boundaries of religion, ethnicity, and geographical origin. This was evident in both structured activities and casual interactions at the center, which served as a refuge from the pressures of conforming to Bosnian societal divisions while simultaneously providing space to meaningfully engage with the role of religion in their lives. A particularly illuminating example was a field trip I joined to various religious sites—including a mosque, an Orthodox church, and a Catholic church—which enabled participants to actively reclaim parts of the city they had previously considered off-limits. For most students, this marked their first visit to a place of worship of another faith, largely due to perceived barriers of welcome.

Figure 6: Participants, peer educators, and volunteers pictured during the visit to the Gazi Husrev-beg mosque in Sarajevo (Source: Minahil Mahmud personal photos)

The center also functioned as a vital space for identity formation and reflection. Identity-focused workshops proved especially impactful, encouraging participants to explore aspects of themselves beyond their religious and ethnic affiliations. As one participant, Mateja, noted, “I enjoyed the workshops about our identities. More than 90% of us didn’t mention our religion as our identities. But mostly it’s stuff like art, what we enjoy, and that’s when you realize how similar we are.” She went on to say:

Our religion doesn't define us. It’s only one aspect of us. So, we should understand it, and we should learn about each other more, (focus group, June 12, 2024).

This perspective was reinforced in my focus groups, where students naturally gravitated toward discussing their hobbies, hometowns, and career aspirations rather than their religious or ethnic backgrounds.

Importantly, this approach does not represent a rejection or erasure of religious identity. As a Catholic institution, faith remains central to the Youth Center’s mission. Rather, the program emphasizes finding common ground through religious differences, not in spite of them. As administrator Zelkjo Maksimovic emphasized, “You have to find out what your religion is, in order to have understanding in someone else. That’s the first step” (interview, June 26, 2024). This sentiment was echoed by a participant in my focus group who shared, “I honestly don’t care what religion you are. I care about: ‘are you a good person?’ I am religious, I love my religion, but we need to be friends with other religions too” (focus group, June 12, 2024).

The program’s peer educators and staff consistently modeled this inclusive mindset, making it an integral part of the center’s culture. Even in initial icebreaker activities, students were encouraged to form groups based on shared interests and experiences—such as being a sibling, enjoying art, or playing sports—rather than traditional demographic markers. As peer educator Ejub explained, these activities aim to help students discover commonalities with those they might consider different from themselves (interview June 19, 2024).

The program incorporated diverse activities that encouraged interaction and mutual understanding. These included a creative “bridge-building” exercise where students were randomly assigned to groups and challenged to design cardboard bridges, with each team competing to construct the structure that could withstand the most weight. A lively Bosnian singing competition further broke down social barriers, while a hiking trip in Travnik provided opportunities for shared experiences outside the center’s walls. However, what struck me most profoundly was the genuine comfort and camaraderie participants displayed during their leisure time. They would often gather informally, engaging in deep conversations that stretched late into the evening, revealing the authentic connections they had formed.

Figure 7: A group of around 30 young people sits in a circle of chairs inside a large, well-lit room. They appear to be participating in a workshop or group discussion. One person, an adult facilitator, is speaking while others listen. (Source: Minahil Mahmud personal photos)

Notably, while the leaders and staff of the program articulated a need for Bosnian youth to unlearn prejudices and break out of monoethnic silos, the young people I spoke to demonstrated a very clear understanding of the forces they believe are keeping them apart and were proactive about correcting this by seeking out the interreligious program. This is best encapsulated in a quote from one of the project coordinators, Stefan Kukrić:

They’re special because they want it. They need interaction with young people from another religion. That’s the most beautiful thing I can see, (interview, June 26, 2024).

By seeking out the program, these young people are taking a step towards connection and community building. They do not subscribe to the prejudices of previous generations who lived through the war because the war is not their touchstone. They also embody a sense of service and a commitment to share their ideas of tolerance and peacebuilding with their friends and families. Very often, the Center accompanies them on this journey and provides resources and support for projects they start when they return home.

My observations illuminated a crucial insight: interreligious dialogue is not merely a theoretical construct as often conceptualized in academic settings, but rather a living practice—a “how” rather than a “what.” Through their daily interactions and activities, these young people were actively demonstrating how religious identity can serve as a bridge rather than a barrier to understanding and connection.

Partnership with Bosnian Schools: Complicated but Essential

Schools play a critical role in the Youth Center’s work, but they also represent a significant challenge. Today, more than 50 schools across Bosnia operate under a system of ethnic segregation known as Two Schools Under One Roof. Students enrolled in this system are separated based on their religious and ethnic identities, even when they occupy the same school building.

A participant in my focus group shared what it was like to experience this system: “I went to elementary school for nine years and I never saw Bosniaks. We were completely divided. Even though it’s the same building, we never had the same classes. We even had different professors. Everything was completely different. It’s like we never met them” (focus group, June 12, 2024). Peer educator Ejub described the dangerous implications of segregation in education: “Unfortunately, the system here is telling us that two different people from different religious backgrounds cannot coexist in one classroom” (interview, June 19, 2024). These divisions extend far beyond school walls, creating a cycle where limited interaction breeds continued separation, ultimately constraining students’ social experiences and understanding of one another.

Similar to the political arrangement of the Dayton Accords, Two Schools Under One Roof was meant to be a provisional arrangement. After the end of the war, the system “brought children of different ethnicities, who had previously studied separately, into a single building—a temporary solution implemented in an extremely sensitive post-war context and considered only a first step toward full integration of schools.” However, thirty years after the end of the war, despite repeated efforts to end the system, segregation has become a permanent feature in many schools.

Figure 8: A map of Bosnia and Herzegovina highlighting locations of the "Two Schools Under One Roof" system, an educational arrangement where students from different ethnic groups attend the same school building but are taught separately. The map marks 13 municipalities across three cantons: Zenica-Doboj (Maglaj, Žepče), Central Bosnia (Bugojno, Busovača, Fojnica, Gornji Vakuf-Uskoplje, Jajce, Kiseljak, Vitez), and Herzegovina-Neretva (Čapljina, Mostar, Prozor-Rama, Stolac). These areas are shaded in pink, with municipal names labeled in blue. (Source: Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe: Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina)

The Youth Center has developed creative strategies to work around these challenges. They actively recruit students by sending representatives, often former program participants, to speak in schools. Rev. Šimo explained, “We do work with the schools. That’s excellent. So we send to the school our program and then they invite us to come and to speak to the classes about this theme of peace and reconciliation” (interview, June 22, 2024).

This recruitment strategy also helps address parental concerns. Many parents are initially hesitant about their children participating in interreligious programs. By working directly through schools, the Youth Center can reach students who might otherwise be prevented from joining.

The more that schools fail to provide what students need, the demand for what the Youth Center offers rises. Participants consistently highlighted the center’s unique offering: a space to discuss topics typically avoided in traditional classrooms. One participant shared, “In my school we have politics but the professor reads a book and that’s it. Nothing new, nothing interesting. And here I believe, you learn a lot of interesting things about politics, about everything I wanted to know. And then of course, in the religious programs, I learned about religions or some traditions of different parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina and I really learned some new things about my faith, my culture that I did not know about because it’s different in different parts of Bosnia” (focus group, June 12, 2024).

Mental health emerged as another critical area where the center fills a crucial gap. “I like that here, last time we met here, they talk about mental health and stuff like that, that every teenager should learn. And our school is not interested in that topic,” one participant noted (focus group, June 12, 2024). Another added, “This is the first time talking about depression and anxiety, which many schools don’t mention. I think that’s important for us” (focus group, June 12, 2024).

Participants also appreciated the center’s ability to provide experiences that their schools did not. “I never visited a church, especially in Bosnia. And I think it was a nice experience to have because my school doesn’t really offer those experiences,” one participant remarked (focus group, June 21, 2024).

Looking forward, the ideal outcome is for schools to evolve and adapt. As Ejub, a peer educator, articulated: “We should ensure that every school visits mosques, Orthodox churches, Catholic churches, Jewish synagogues, and places where different ethno-religious groups lost their lives during the war. We should develop a culture of remembering” (interview, June 19, 2024).

The vision is clear: schools should eventually serve the same purpose as the Youth Center, making such specialized programs unnecessary. The current segregated system is a significant obstacle to peacemaking, and addressing it is crucial for genuine reconciliation.

For now, the relationship between schools and the Youth Center remains essential. Schools are a key recruitment ground, both through intentional outreach and word of mouth among students. Despite challenges like administrative bureaucracy and systemic segregation, the center continues its work as a critical bridge, offering the integrated, experiential peace education that the formal system has yet to fully embrace.

Nurturing Leadership from Within: The Transformative Role of Peer Educators

Figure 9: A group of around 20 young people sit in a circle on the floor of a well-lit room with wooden benches and large windows. Two people in the foreground are playing acoustic guitars. Most participants are holding papers, likely song sheets. Green foam mats are spread on the tiled floor for seating. (Source: John Paul II Youth Pastoral Center).

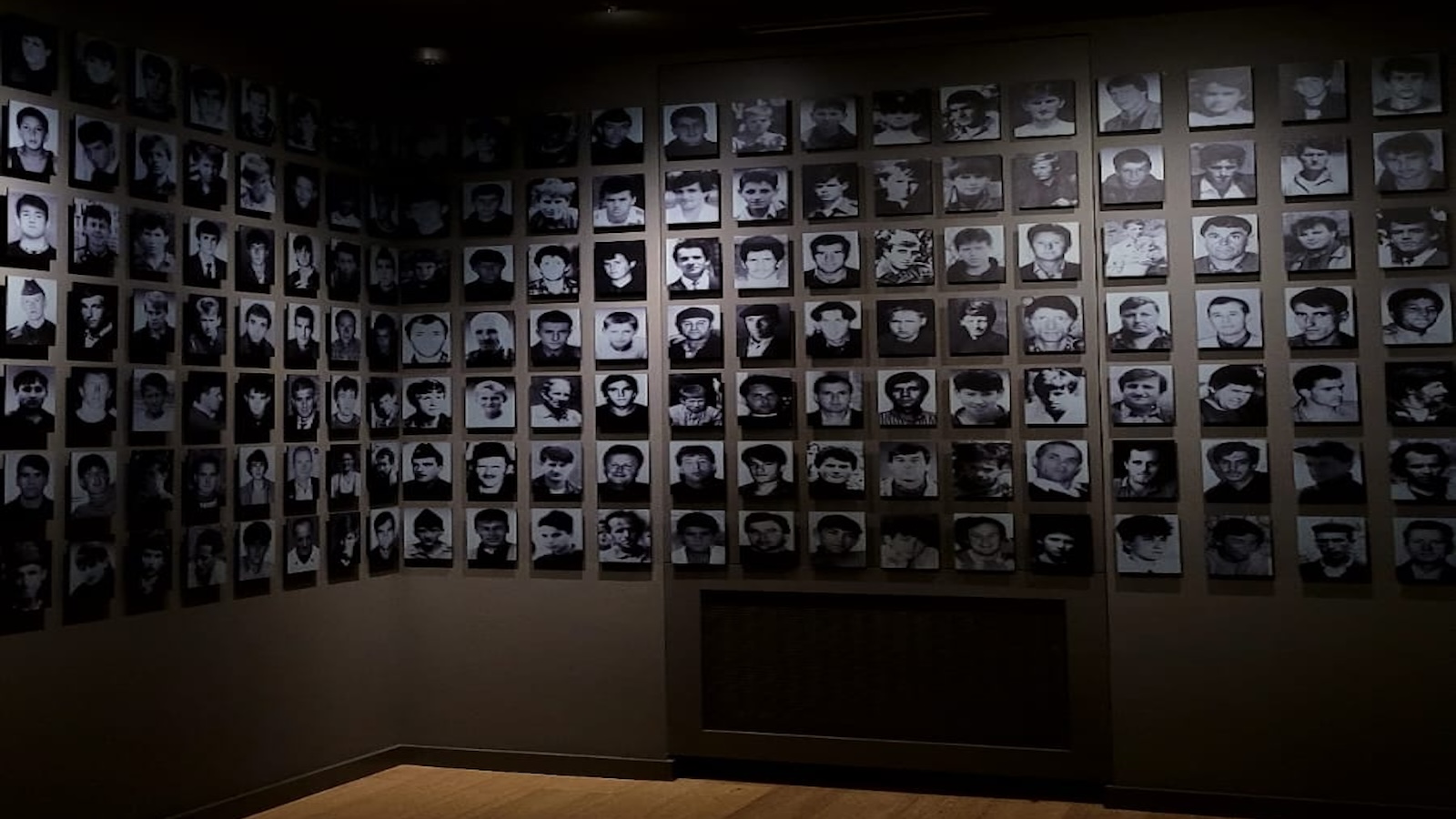

At the heart of the Youth Center’s success lies a unique and powerful model of leadership: peer educators. These young volunteers are more than just program facilitators—they are the backbone of the organization, creating a sustainable cycle of community building and personal growth.

The volunteer position attracts remarkable young people driven by deeply personal motivations. Angela Dizdar, a peer educator who had just finished high school, traced her inspiration to childhood memories of summer camp volunteers who made a profound impact. “When I was little, in my church there was this thing called Children's Summer. They were always there for us, they were fun,” she recalled. “When you're 10 years old and someone gives you chocolate and a ball, it’s the world for you. So from that moment, I wanted to be them to someone” (interview, June 19, 2024).

This personal connection to community service is not unique to Angela but represents a broader pattern of engagement within the center’s ecosystem. The leadership pathway follows a distinctive progression that sets it apart from traditional institutional models. Center leaders typically begin as program participants, often returning year after year. Martina Vidovic, now an administrator, exemplifies this journey: “I joined actually every year during my high school, it was four years, I joined summer camp. And then after, I decided to become a peer educator here in the Youth Center” (interview, June 21, 2024).

Martina’s trajectory is mirrored by others, such as Zeljko Maksimovic, who further illustrates the center’s organic approach to leadership development. Having served as a peer educator from 2019 to 2024, he recently transitioned to an administrative role when an opening became available: “Two months ago there was an opening for a job and they called me” (interview, June 21, 2024). This internal progression demonstrates a commitment to nurturing talent from within, transforming volunteers into professional leaders.

Beyond volunteering, the peer educator model offers substantive professional development. Participants gain practical skills in workshop facilitation, public speaking, and project management—valuable experiences for high school and university graduates. Moreover, they find a supportive professional community that often leads to employment opportunities within the center itself.

The approach represents a radical departure from traditional educational hierarchies in Bosnia. Unlike formal school settings, peer educators blur the lines between authority and friendship. During my observations, they were seen laughing and dining with students between sessions, creating an environment of approachability and trust. Students feel comfortable sharing personal challenges with these mentors who are close in age yet still serve as role models.

Recruitment and community engagement are equally innovative aspects of the peer educator role. They often visit schools to share their experiences, serving as the center’s first point of contact for potential participants. Their personal stories make the center’s mission tangible and compelling for the students, bridging institutional outreach with authentic personal narratives.

The profound impact of this model becomes evident through participants’ aspirations. During my focus group, every single participant expressed a desire to return as a peer educator. Manuel, a second-time program participant at the center, captured this sentiment: “I hope to be a peer educator next year… to actually be part of this center and this amazing community” (interview, June 22, 2024). Martina further reflected on this organic progression: “When the participants see what we do here, they want to be part of it, and maybe to teach others something” (interview, June 21, 2024). The unanimous desire of participants to give back reveals the profound ripple effect of the peer educator program.

This creates a self-sustaining cycle where leadership emerges naturally from within, strengthening the Youth Center’s impact across generations. The administrative team itself embodies this principle, with leaders like Martina and Zeljko having begun as program participants. Their journey underscores the institution’s culture—an evolving, welcoming space with open doors for members who become integral parts of its mission.

Ultimately, the peer educator model transcends traditional recruitment strategies. It represents a revolutionary approach to youth leadership that breaks down hierarchical barriers, provides comprehensive skill development, and creates continuous paths for engagement.

Figure 10: Infographic titled ‘From Participants to Leaders: Cultivating Sustainable Leadership’ showing a four-stage progression pathway from left to right. Each stage includes a supporting quote from a participant, peer educator, or administrator, demonstrating the journey from participant to community leader. The stages progress through: (1) Joining as a Participant, where members first enter the program ["I really learned some new things about my faith, my culture that I did not know about"]; (2) Discovering a Passion for Leadership, where participants develop interest in leading others ["I hope to be a peer educator next year to be part of this amazing community"]; (3) Becoming a Peer Educator, where they take on teaching and mentoring roles ["We [peer educators] are like more with the kids, you know, if someone has a stomach ache, if someone doesn't feel well, they come first to us"]; and (4) Expanding the Ripple Effect, where they help sustain and grow the community ["When the participants see what we do here, they want to be part of it and maybe to teach others something"]. (Source: Minahil Mahmud)

Envisioning a Future Beyond the Need for Peacebuilding Programs

The “Let’s Step Forward Together” program revealed three critical insights into peacebuilding and youth engagement in post-conflict Bosnia. First, the research demonstrated that interreligious dialogue is not a theoretical concept, but a living, experiential process. Participants consistently formed friendships that transcended societal divisions, challenging historical ethnic and religious boundaries by focusing on shared experiences, interests, and personal identities rather than demographic labels.

The study also illuminated the profound challenges within Bosnia’s educational system, particularly the Two Schools Under One Roof segregation model. Despite these systemic barriers, the Youth Center developed innovative strategies to bring young people together, addressing critical gaps in formal education. The center is a vital space for exploring topics typically avoided in traditional classrooms, including mental health, politics, and peace-building.

The peer educator model emerged as a transformative approach to youth leadership, creating a self-sustaining cycle of engagement. This model turns program participants into mentors, providing professional development opportunities and fostering a deep sense of community and purpose. By breaking down traditional hierarchical structures, the program empowers young people to become active agents of social change.

The potential for this approach extends beyond Bosnia’s immediate context. The program’s methodology of prioritizing personal connections and youth-led initiatives could be particularly valuable in other regions struggling with social division and historical tensions. The ultimate vision, as articulated by program coordinators, is to create a future where such specialized interreligious programs become unnecessary—a powerful goal of complete social integration.

Future development could focus on scaling and replicating the model as well as conducting longitudinal research to measure long-term social impact. The challenges remain significant, including systemic resistance, generational trauma, and deeply entrenched political barriers. Yet the participants’ experiences suggest a compelling alternative narrative—one where young people actively choose connection over division.

As program coordinator Zeljko poignantly expressed, the hope is that one day, such projects will be “useless” in Bosnia—meaning true integration and understanding will have been achieved (interview, June 26, 2024). This vision represents more than an educational initiative; it is a living demonstration of how personal relationships can bridge seemingly insurmountable divides, offering a powerful model of grassroots peace-building.

Figure 11: An exterior view of the John Paul II Youth Center. The picture shows a modern, multi-story building with a layered architectural design. The structure features a mix of red, white, and brown panels with numerous balconies and windows. In front, several flags are visible, including one with religious symbols. The building is surrounded by greenery and is partially enclosed by a black gate, with a mural of a heart and child painted near the entrance. It is a bright, sunny day with a clear blue sky.

The views expressed in this student research are those of the author(s) and not of the Berkley Center or Georgetown University.

Featured Person: Minahil Mahmud Person